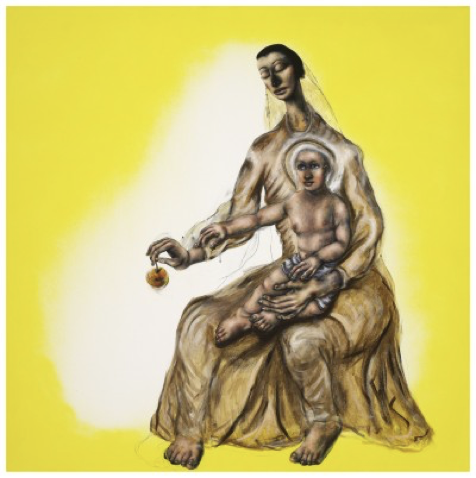

Reflections from Sunday 21 June - Trinity 2 - the texts were: Jeremiah 20: 7-13 and Matthew 10: 24-39. Thinking about the connotations of 'A is for Apple' held in Eve's hand and ours, and in the hand of Mary and Jesus reaches out to take it; and reflecting to on how we employ our freedom.

Reflection One

Apple: A is for apple, so goes the alphabet rhyme. Or perhaps the old wives tale: an apple a day keeps the doctor away. Motherhood and apple pie, something good and important.

Harvested and baked under crumble with lashings of custard; pressed into sweetness for refreshing juice; or fermented a while longer for the stronger cider.

A is for apple. It's appealing, enticing.

Enticing to the point of seduction; to the point of temptation.

Eve was here - Chris Gollon

Eve. Was. Here.

Eve took.

It looked so good. So healthy. So enticing.

But this apple wasn’t pressed into sweetness; it had a bitter taste.

A is for apple. Our tendency to take what we desire. Our human capacity to consume.

For freedom is enticing; even though we risk turning away from God and others, getting caught up in ‘stuff’.

In the words of opening hymn we seek forgiveness for our foolish ways; asking God to breath through the heats of our desire.

Image: unknown

We are not immune from it. The MacBook through which I see you; the iPhone from which I’m reading carries the mark of that bitten apple. It’s the signifier for our quest for knowledge; it marks out a brand.

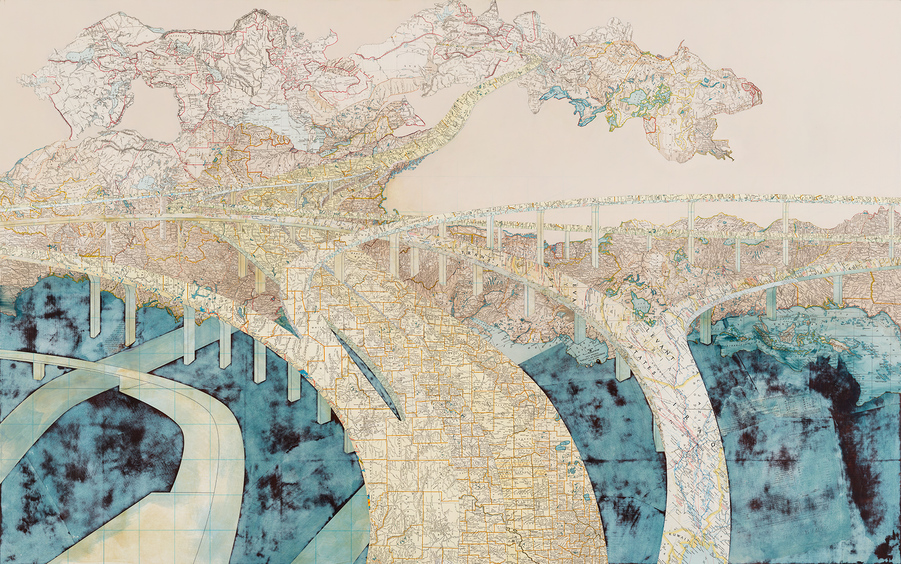

Map [Matthew Cussick]: As human beings we face countless decisions; and find ourselves pulled in multiple directions; seeking meaning, knowledge, purpose and identity.

Chasing the Dragon - Matthew Cusick

It can feel conflictual: not so much a cross roads but a spaghetti junction of decisions and desires; fears and freedoms.

And as we think about what we stand up for and what we call out, those desires and fears and freedoms come under pressure. We might be enticed to do the thing that’s most expedient or which makes life easier.

It can be tempting to ask: what does this do for my professional reputation or for my popularity? Who will I offend or what will it cost?

These are the kind of questions facing Jeremiah.

Jeremiah [San Francisco, Grace Cathedral]

We encounter him today reflecting on God’s call to be a prophet - to be one who called people back to God’s ways of love. As a prophet he exhorted God’s people to be faithful to the commandments and to make love visible in public through the pursuit of justice.

The language he uses is of being enticed and empowered by God’s call. It was compelling and he could do no other than say ‘yes’ to this work, this life of costly service.

In the words in the stained glass window from Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, he employed his freedom. He employees his freedom to serve God in a particular way.

But it was a challenging task. It made him a laughing stock. It was not popular.

He was mocked for calling out the violence done through failure to do what was just, merciful and compassionate.

He was mocked for naming the destruction caused by the refusal to obey the commandment to love.

He spoke, cried out and shouted.

And the very thing he loved - the word and life and love of God - became a source of derision.

It felt as if this calling had cost him everything: influence, friends, status and reputation.

He’d employed his freedom.

So when he’s temped to give up, the original burning conviction wells up within him. He cannot to anything else but speak up for the needed, abused and marginalised.

And yet, when enticed by those who are watching for him to stumble, he remains steadfast. However wearied he is, he won’t abandon this long labour of seeking what is right.

He has employed his freedom to God’s cause.

Unity of Praise - Jackie O Kelley

Jeremiah’s moment of crisis, his grappling with the cost of his work, reveals to us something that it as the heart of today’s discomforting gospel.

It is an illusion to think that seeking God’s ways of peace means a comfortable life.

We have each been called by name; we have employed our freedom to God’s ways. And like Jeremiah there are times when we might waver or feel enticed to seek an easier path.

But Jeremiah reminds us, as long as the fight for what is just continues, we will somehow find peace in that struggle.

It’s not comfortable or painless: but on Jeremiah’s lips those cries for what is just turn to praise. For God will deliver the lives of the exploited and overlooked, the discriminated against and the marginalised.

We’ve heard that song of praise: of laudamus the - we praise, bless, adore and glorify the Lord our God; and now we hear another song, which reminds us that God is among us.

God is with the broken and the weak and in the spaces in between.

Reflection Two

In this curious and challenge set of teaching, takes us to the heart of how we are to employ our freedom: not in competition with others for the their sake.

Jesus takes what is whispered and invites us to share it from the roof tops. There is no zero sum game in God’s economy; we do not live out of scarcity of love but out of an abundance that calls us to seek justice.

Do we hear God’s voice cry out? Are we listening? Do we come together with the ones without a voice, the forgotten and ignored?

In this, we are one flesh. Whatever our gender, class, race, sexuality, wealth, age or health.

We live in Christ. We are one flesh. And by the power of the Spirit, we are to listen.

To listen to what entices us, and to ask, is this the way of God?

To listen to what entices us, and ask if it names the dignity and equality of others.

To listen to what entices us, and to seek what it is a blessing for all.

We all have a share in these tasks: and for some of us, because of the stories we’ve been told, it’s a time to listen; for some of us, because of the stories we’ve been told, it’s a time to be heard.

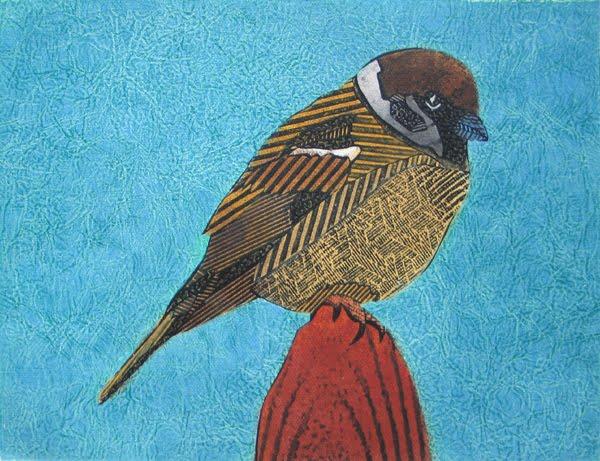

Sparrow Bonnie Murray

That process of speaking and being heard takes time. It doesn’t just happen in the public square but in our one to one relationships.

Jesus moves us from the public realm of our rooftops; to the intrinsic value of every human life. He invites us to look upon a sparrow. To see the thing that is small and seemingly insignificant; and to know that God’s tender care for even the tiniest thing extends also to us.

Just as the sparrow is precious, so are we: God knows the hairs of our head, the thoughts of our hearts, our cries and our songs. Dare we extend that loving regard to each other - seeing each other as who we are - with our burdens and privileges, our gifts and our needs?

And seeing each other dare we employ our freedom as members of one body, to stand against all the harmful longings of the flesh that entice us - of power used for self.

Dare we do this, together, hearing our stories: hearing the hope and challenge, the cries and dreams. For in this we find our peace.

Wallsily Kandinsky - Composition VII

The language of peace that Jesus uses is full of conflict and division; it really challenges us about tour priorities.

This image by Kandinsky is full of bold lines, and vibrant colours; it’s full of overlapping forms and shapes. We may not see it immediately, but in it are the biblical themes of the apple tasted in Eden - the moment our longings for power and knowledge enticed. It speaks of judgement - and how we use our freedom; but it also speak of resurrection and the gift of new life.

Jesus speaks of this life that comes when we lose it for his sake, and the sake of God’s kingdom of justice and righteousness. The conflict of which he speaks is not destructive but creative. It is not bent towards destruction, but liberation.

Writing in her book Seeking God, Esther de Wall writes of the stability we find in God’s love for us; it means that we don’t run from where battles are being fought, but that rather we have to stand still where the real issues have to be face.

This way of being is based on Gospel paradox of losing life and finding it.

How do we employ our freedom - for self fulfilment or to the struggle of liberation for all?

Martin Luther King - Huffington Post

Perhaps this is evoked most powerfully - and in a way which frames the question in a practical way - by Martin Luther King. He said: Cowardice asks the question, ‘is it safe?’ Expediency asks the question, ‘is it politic?’ Vanity asks the question, ‘is it popular?’ But conscience asks the question, ‘is it right?’ And there comes a time when one must a position that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular, but one must take it because one’s conscience tell one that it is right.

We are called to do what is right. To listen carefully and to be willing to change; to cry out in the expectation that we will be heard; to sing a song that brings joy and hope.

Are you a caregiver: nurture and nourish people around me via creation and sustaining community of care, joy and connection.

Or perhaps your freedom is employed in being a disrupter: taking uncomfortable or risky actions to shake up the status quo, raise awareness and build power.

Do you like to teach and guide - using gifts of discernment and wisdom?

Are you called to the work of telling stories - sharing experience and histories in words and art in order to shape a community moving forward together?

Or are you visionary - setting out possibilities, hopes and dreams, reminding us of our direction?

Are you someone who helps us weave lives together? Or someone gifted in tending to the traumas of oppression and isolation?

We need all these gifts - deploying our individual freedoms for the sake of God’s call to love, justice and mercy.

Madonna and child - Chris Gollon

And we do it not in our own strength. But because God so loved the world. So loved the world that God’s very self dwelt among us in flesh of our flesh. Taking the apple.

The apple in our hand reflects our tendency to mess things up; the apple in the hand of Mary, as Jesus reaches out to take it, reflects God’s capacity to love and forgive.

Let us pray:

Lord, you have taught us that all our doings without love are nothing worth:

send your Holy Spirit and pour into our hearts that most excellent gift of love,the true bond of peace and of all virtues,

without which whoever lives is counted dead before you.

Grant this for your only Son Jesus Christ's sake,

who is alive and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever. Amen.

© Julie Gittoes 2020