Advent Sunday 2025: Isaiah 2:1-5, Romans 13:11-14 and Matthew 24: 36-44

A translation of Isaiah 2 by David Rosenberg in A Poet’s Bible:

One day

[. . .]

God

will come forward

to settle the conflicts between us

finally the one

true witness

even the finality of holocaust

will melt away

like lowland snow

the military hardware

translated into monkey bars

where children play

the hardened postures

crumbled

like ancient statues

children will wave through the gunholes

of tanks

rumbling off to the junkyard

people will find hands

in theirs

instead of guns

learn to walk

into their gardens

instead of battle

Oh House of Israel

let’s walk in the sunlight ways

of his presence

Twenty years ago, a sculpture entitled “The Tree of Life” was unveiled in the British Museum. It echoed Isaiah; embodied the prophet’s hope.

This ‘tree’ was made by a group of artists from Mozambique using weapons used during their country’s 17 year civil war: decommissioned AK-47 rifles, pistols and rocket-propelled grenade launchers had been cut up and repurposed to create this symbol of reconciliation after conflict.

This sign of healing, hope and recreation was part of a wider project supported by Christian Aid and run by Transforming Arms into Tools. They employed former child soldiers to dismantle guns. The parts were then swapped locally for everything from building materials to sewing machines, bicycles to farming equipment.

The founder of the project Bishop Dinis Sengulane challenged those who saw the sculpture, saying: ‘we would like you to adapt this to your own reality. People involved in the armament industry, even in making toy guns, should realize that guns are instruments for destroying human life.’

Artists and prophets are inviting us to imagine what we might do if we lived in a world where war ceased. What would we do with the money and resources, skill and energy?

As with our news cycles, so with Isaiah, human beings too often exchange bold vision for old ways. Yet in the face of that painful reality, such a vision keeps hope alive. Maybe it even burns brighter in uncertain times.

One of the gifts of Advent is that it gives us space to acknowledge what we experience now and also what God intends for the future. It reminds us of what is possible: that love can cast out fear. Something sacred might be built when swords become ploughs, guns exchanged for sewing machines.

In the now and not yet, Jesus calls us to stay awake. When the violence that denies his peace is so real and evident, we are to keep our hearts and minds fixed on the hope of his coming. Being alert is not a passive posture. We can choose to live and act and walk in the light of our Lord now.

Being alert, watchful and awake is difficult because we do not know ‘when’ of our Lord’s coming. We risk either hypervigilance - or complacency.

How do we live with this knowing, but not knowing?

What does hope look like in the waiting?

Jesus gives us two vivid images: the story of Noah and the flood alongside a homeowner and a thief. They are stories of being prepared and alert; of trusting in God’s justice, refusing to let go of hope.

Noah is so familiar - comforting even - the ark prepared for the animals in their pairs. Perhaps we might be challenged and inspired to think about what we take care of today; as we look at our natural world, what do we preserve and protect, renew and regenerate? [South Wales valleys]

A thief in the night? That feels far more disturbing - especially if you’ve experienced a break-in or theft. It doesn’t sit comfortably as a parable about justice springing up from the earth - or mercy flowing like an everlasting stream.

The image shocks us. It forces us to pay attention - to consider how we use each day, each moment. It’s an invitation to see opportunities to encourage or do good, to bring a little hope in a troubled world. [Advent calendar] It’s a disincentive to letting the minutes run through our hands like sand in an hourglass, indifferent, unmoved.

To be ready or alert, attentive or watchful is about the small things in many ways. It’s a great equaliser. Rather than assuming it is wealth or status that determines the future, we rely on knowing the end of the story.

There will be a tree of life, for the healing of the nations: we live now praying and hoping, advocating and lamenting that the world will see the face of the one who is the judge and arbiter between peoples and nations.

Our lives and bodies and our people and sacred places can be little signs of that: speaking of communion, of sanctuary, of grace.

The day of the Lord is coming - in the midst of parties and shopping, baking and preparing. Advent reminds us of what we know: the one who comes as an infant, the fullness of God with us, is the one who will come again. On that day the fullness of God will be all in all - with the plumb line of truth, forgiveness and healing.

Maybe in Advent our calling is to be “still points” in a frantic world: watching, paying attention, serving; dwelling with God in worship, scripture and prayer. Waiting on Christ. Being united in him with each other.

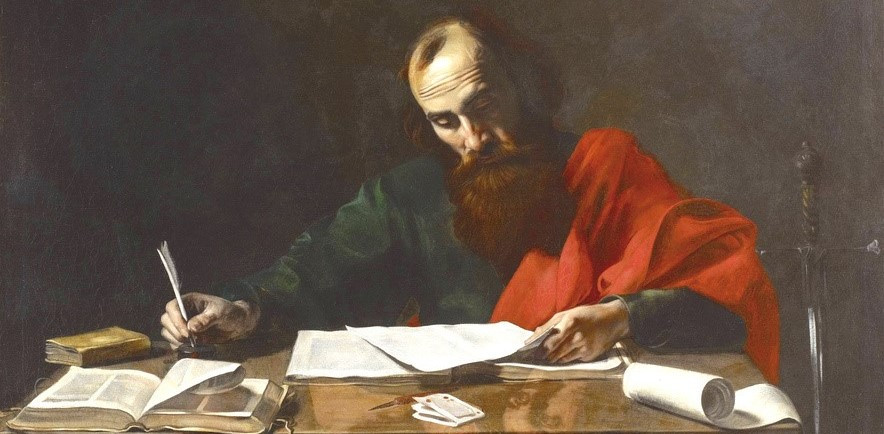

In his letter to the Romans, Paul is teasing out what this might look like. He does that in a series of ‘pairs’.

He begins by contrasting being asleep with being awake, and extends the idea to the realm of different ways of life: being asleep and giving in to one’s own desires; being awake and trying to live accounting to Jesus’ command to love neighbour as ourself.

He turns to the very ordinary habit of dressing and undressing: throwing off those things which ‘don’t look good’ not because of a fashion fail, but because they harm us and others; they don’t reflect God’s will for us. He talks of putting on new clothing as a visible marker of the internal shift, of being clothed with compassion, kindness and self control.

He goes further inviting his hearers to put off or shun works of darkness - and instead to put on armour of light: maybe a spiritual hi-vis of faithfulness and peace.

All this is set against the expectation that our salvation, our healing, is near; but that we don’t know when. As Jesus taught we cannot set a diary date for “The End”, nor do we know when we will die. It's an invitation to live lightly and intensely - not knowing when we let go of life, yet every moment and gesture being of value.

Such uncertainty isn’t a call to either hypervigilance or complacency - but to daily faithfulness, to daily forgiveness. It's to live as if that new world is already here, making love known. The final stanza of Jan Richardson’s ‘Blessing for travelling in the dark’:

That in the darkness there there be a blessing.

That in the shadows there be a welcome.

That in the night you will be encompassed

By the Love that knows your name.

© Julie Gittoes 2025