31st August, Trinity 11: Jeremiah 2:4-13, Hebrews 13:1-8, 15-16 and Luke 14:1, 7-14

At Evensong, I revisited some themes in this sermon through the lens of the readings, anthem and a blog by my friend and colleague Al Barrett (Hodge Hill Vicar). In the face of protest, he writes about his parishes experience of courage, solidarity, listening and care which can be found here. Jesus goes beyond Debrett's guide on manners it is a way into thinking about what binds us together, treading others with dignity, shaping a future around harmony rather than discord. When of Al's reflections is about softening hardening eyes and finding common ground. There is so much more to attend to - listening deeply and acting out of that with hope.

In an uncertain world, where many of us are preoccupied by everyday survival and global challenges, it is easy to dismiss manners as a triviality.

Words from the opening of an article on "why manners matter" from the Debretts website earlier this month. Debrett’s describes itself as a record-keeper and chronicler of British society since 1769; and also an authority of modern manners, from protocol and precedence to etiquette and behaviour.

The article acknowledges that in the past, social codes became weapons to exclude ‘undesirables’ and reinforce social class; but today, they argue that ‘good manners’ - online, professionally and in everyday encounters - are simply a matter of treating others as we would like to be treated.

In that sense, by saying they make the case for manners being [quote] a positive beacon in times of upheaval and transition… an indication of thoughtfulness and empathy, a desire to find social harmony and agreeableness rather than discord and friction.

Thinking about table manners and social etiquette in the light of Jesus’ interactions in today’s gospel doesn’t map onto the world of Debrett’s: on the one hand, Jesus is routinely exploring with those he meets what it means to love one’s neighbour; but on the other, his interventions can be provocative and demanding.

Over the course of his ministry, he accepted many dinner invitations as a guest - eating with friends or joining those who held positions of authority. He kept company with those not considered respectable or part of the right crowd. He noticed what was going on and said what no-one wanted to hear.

Sometimes there were moments of disruption or interruption as his hosts were joined by those seeking forgiveness or healing or the woman anointing his feet with tears. On other occasions, he acted as host, whilst also taking on the role of servant. Sometimes others picked him or his disciples up on whether they were following the correct customs like ritual washing.

In today’s gospel, he’s been invited for a Sabbath meal. He watches how his fellow guests behave and notices how they jostle for honoured places next to the host. Maybe we can recall similar situations at work-dos or family gatherings.

He watches them consumed with choosing the places of honour and tells them a story: echoing the reaching of Proverbs, he speaks of humility rather than self-promotion or self-assertion.

It sounds like a common sense approach to manners - something that would sit alongside how Debrett’s talks about the road to social success. In their terms, consideration and attentiveness makes people likeable. Making others feel comfortable and at ease, they write, means you’re less likely to patronise other people, put them down or shore up your shaky self-confidence by bullying or dominating behaviour.

Jesus goes further. He turns from parable to direct advice: share hospitality with those who cannot repay you; invite into your social space those who cannot invite you back. He undercuts the social status quo and extends a circle of blessing.

Luke doesn’t record the reaction of those at the table with Jesus: did they ask questions or enter into a discussion? Or was there an awkward silence before the host steered the conversation towards something less contentious?

No doubt his words will land with us in different ways - surprise or discomfort, or perhaps relief or curiosity about how we shape our life together differently.

There is something liberating about subverting the demands to schmooze or compete for attention. There is something challenging about opening our hearts to those who are different from us, or who can’t do us a favour.

God does not want us caught up in a game of social snakes and ladders: weighing connections, chances and risks in relation to status, popularity, influence; any of the ways in which we weigh who’s the greatest.

All that becomes "great" then are our levels of competition, mistrust, indifference and anxiety. It is anti-social - a weakening of social bonds; reduced reciprocity and recognition.

Instead Jesus promises not only a table, but a kingdom where we all find seats of honour: a place where we are already known, loved, forgiven, restored. It is a place marked by humility and generosity; by the risk of hospitality rather than fear.

This is not easy. It requires conviction, patience and sustained effort - including listening carefully. It's why our partnership with North London Citizens matter, increasing our capacity to listen.

The article in Debrett’s ends with a conclusion entitled ‘pay attention’. Being alert and observant; opting into social interactions, rather than disengaging from the people around us; using manners as channels of positivity and good will.

The final line is striking [quote]: Life on our crowded planet is increasingly hectic and challenging and now, more than ever,we need to moderate our behaviour and promote civility and courtesy.

Hectic and challenging might sound like an understatement given the social, economic and political and environmental pressures that confront us. It’s a complex web - aging populations, falling birthrates, patterns of migration.

All that and more impacts upon each of us personally and our collective lives and responsibilities. They shape how we see the past, our present hopes and concerns and also the vision of our future life across villages, towns and cities.

In an article published yesterday, Rowan Williams names the chaos and under-resourcing of legal processes; the conditions that lead to insecurity and rootlessness and at worst resentment and criminality; and the lethal systems rather than safe routes which means integration can’t be planned, trapping asylum seekers in ‘a situation both dehumanising for them and challenging for the localities in which they are placed’.

He calls for a better cross-party conversation. But he also suggests that an urgent priority in the standoff between the ordinary and alien is opportunities to ‘help each other to recognise in the other some of the shared experience of being silenced and vulnerable.’

There is something about the way in which we eat together Sunday by Sunday - in communion with God and each other - that begins to form our social imaginations. A place of shared vulnerability; where we can listen and speak.

We stand on holy ground: dazzling and disorientating. We need to tread carefully. We need to be full of care to attend to what it is we fear - and what kind of future we want.

There is no pecking order or hierarchy around this table, we humbly and hopefully extend our hands or bow our heads to receive the same food, the same blessing. This is the palace where Chrsit’s sacrifice of love draws us into pardon and peace; giving us a firm foundation to base our lives on.

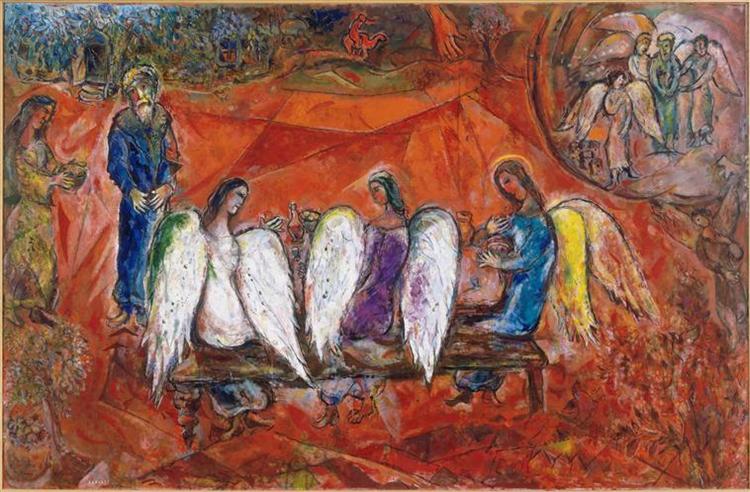

To be drawn into something so radically different is both an experience of immense grace and also an unsettling challenge. It reminds us that our encounter with the stranger, the one who cannot repay, might be the moment we entertain angels unawares.

Hebrews speaks of mutual love continuing. It’s the kind of love that invites us to remember the stranger - the imprisoned, the tortured, those whose lives and experiences might be far removed from what we experience. Or for some, an experience very close to their own trauma.

It’s the kind of mutual love that honours marriage with an invitation to fidelity which might shape all our households and relationships.

Mutual love is also known in contentment - shunning pursuit of money for its own sake with the freedom of trusting in God. If mutual love is a form of good manners, then the writer of the Hebrews stretches the guidance of Debrett’s to not only doing good, but sharing what we have.

In the face of upheaval and transition we continue to eat together here, at this table. Our desire to find social harmony is kindled by the one who gave himself for us.

His self-giving love draws us into agreeableness rather than friction - though we are many, we are one body; a moment of faction, of breaking, becomes the place of our wholeness. We glimpse, for a moment, the possibility of it.

To break bread together is an indication of thoughtfulness and empathy that begins not with the good manners of Debrett’s but in the heart of a God who loves us and draws us to Godself in Christ.

In homes, cafes, canteens we continue to eat with friends and strangers. At this table, God’s grace renews our humanity and gives us something to take pride in; finding safety and dignity in the ordinariness of our lives, the lives of others and the life of our community.

© Julie Gittoes 2025