Passion Sunday

We adore you, O Christ, as we bless you,

for by your holy cross you have redeemed the world

TODAY is Passion Sunday. As we move towards the end of Lent, our focus turns to the cross. It is such a familiar symbol to us - we wear it as a treasured item of jewellery, it adorns our churches and we remember that in baptism we too are marked with the sign of the cross. For Christians, the cross becomes a sign not only of Jesus’ suffering and God being with us in ours; but it also points to life and hope, healing and redemption.

The word ‘passion’ conjures up perhaps intense feelings or energy, strong convictions or a deep commitment to an interest, hobby or person. In this season, passion is the lens through which we see afresh the depth of God’s love for us. Love that is a profound commitment to be with us in the midst of suffering and death.

We enter into this time of our Lord’s passion, acutely aware of the reality of illness and death due to the Coronavirus; and perhaps aware of our own vulnerability too. Our readings take us to a place of dry bones and to a tomb. Perhaps they allow us both to acknowledge our reality, along with the pain of separation; may they also give us hope - there will be connection and life again; for love is stronger than death.

To focus on Christ’s Passion increases our capacity to be compassionate. As today’s post communion prayer says, what we do for our brothers and sisters we do also for God. Sometimes that means sharing in or being with them in intense emotion. Many people are weeping today, and in today’s Gospel, Jesus also weeps. Pope Francis has called today the “Sunday of Tears”

Today, we make space and time in our own homes to pray and to reflect on the readings for this Sunday. This is a journey for all of us; together we will be learning how to pray for, support, encourage and care for each other.

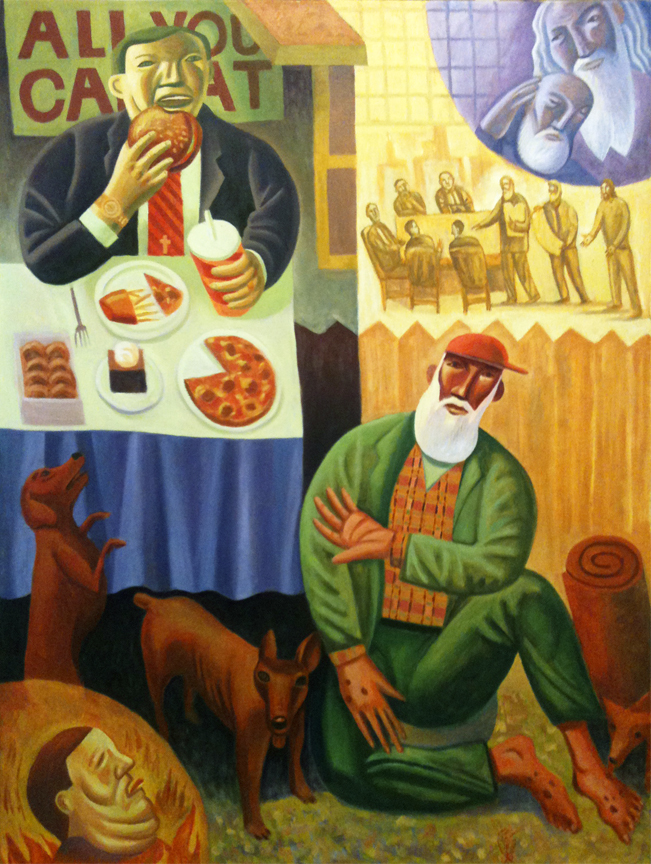

As well as the readings and short reflections, I have also included to images: one from the Jesus MAFA which was an art project based in Cameroon; the other an image taken from the Methodist Art Collection.

As we read, alone or in company, we might want to use an ancient practice called ‘lectio divina’ or divine reading. First, read the text slowly - aloud or silently - and notice what word or phrase holds your attention. Then, sit with that word or phrase in silence. Read the text again and then reflect on what the Spirit might be prompting you to think about or do.

We begin with today’s prayer for the day - which ‘collects’ together the themes at the heart of this Passion Sunday.

The Collect

Most merciful God,

who by the death and resurrection

of your Son Jesus Christ delivered and saved the world:

grant that by faith in him who suffered on the cross

we may triumph in the power of his victory;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and forever

You might want to read all three texts before reflecting; or focus on one, perhaps coming back to others over the day or week ahead. Note that the Gospel is quite a long passage; so you may want to focus on that, or return to during the day/week.

Ezekiel 37:1-14

The hand of the Lord came upon me, and he brought me out by the spirit of the Lord and set me down in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. He led me all round them; there were very many lying in the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, ‘Mortal, can these bones live?’ I answered, ‘O Lord God, you know.’ Then he said to me, ‘Prophesy to these bones, and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. Thus says the Lord God to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. I will lay sinews on you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the Lord.’

So I prophesied as I had been commanded; and as I prophesied, suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone. I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had come upon them, and skin had covered them; but there was no breath in them. Then he said to me, ‘Prophesy to the breath, prophesy, mortal, and say to the breath: Thus says the Lord God: Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live.’ I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude.

Then he said to me, ‘Mortal, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They say, “Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.” Therefore prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord God: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. And you shall know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people. I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken and will act, says the Lord.’

Romans 8:6-11

To set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace. For this reason the mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God; it does not submit to God’s law—indeed it cannot, and those who are in the flesh cannot please God.

But you are not in the flesh; you are in the Spirit, since the Spirit of God dwells in you. Anyone who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to him. But if Christ is in you, though the body is dead because of sin, the Spirit is life because of righteousness. If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also through his Spirit that dwells in you.

John 11:1-45

Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha. Mary was the one who anointed the Lord with perfume and wiped his feet with her hair; her brother Lazarus was ill. So the sisters sent a message to Jesus, ‘Lord, he whom you love is ill.’ But when Jesus heard it, he said, ‘This illness does not lead to death; rather it is for God’s glory, so that the Son of God may be glorified through it.’ Accordingly, though Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus, after having heard that Lazarus was ill, he stayed two days longer in the place where he was.

Then after this he said to the disciples, ‘Let us go to Judea again.’ The disciples said to him, ‘Rabbi, the Jews were just now trying to stone you, and are you going there again?’ Jesus answered, ‘Are there not twelve hours of daylight? Those who walk during the day do not stumble, because they see the light of this world. But those who walk at night stumble, because the light is not in them.’ After saying this, he told them, ‘Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I am going there to awaken him.’ The disciples said to him, ‘Lord, if he has fallen asleep, he will be all right.’ Jesus, however, had been speaking about his death, but they thought that he was referring merely to sleep. Then Jesus told them plainly, ‘Lazarus is dead. For your sake I am glad I was not there, so that you may believe. But let us go to him.’ Thomas, who was called the Twin, said to his fellow-disciples, ‘Let us also go, that we may die with him.’

When Jesus arrived, he found that Lazarus had already been in the tomb for four days. Now Bethany was near Jerusalem, some two miles away, and many of the Jews had come to Martha and Mary to console them about their brother. When Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went and met him, while Mary stayed at home. Martha said to Jesus, ‘Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died. But even now I know that God will give you whatever you ask of him.’ Jesus said to her, ‘Your brother will rise again.’ Martha said to him, ‘I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.’ Jesus said to her, ‘I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?’ She said to him, ‘Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.’

When she had said this, she went back and called her sister Mary, and told her privately, ‘The Teacher is here and is calling for you.’ And when she heard it, she got up quickly and went to him. Now Jesus had not yet come to the village, but was still at the place where Martha had met him. The Jews who were with her in the house, consoling her, saw Mary get up quickly and go out. They followed her because they thought that she was going to the tomb to weep there. When Mary came where Jesus was and saw him, she knelt at his feet and said to him, ‘Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.’ When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. He said, ‘Where have you laid him?’ They said to him, ‘Lord, come and see.’ Jesus began to weep. So the Jews said, ‘See how he loved him!’ But some of them said, ‘Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?’

Then Jesus, again greatly disturbed, came to the tomb. It was a cave, and a stone was lying against it. Jesus said, ‘Take away the stone.’ Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, ‘Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead for four days.’ Jesus said to her, ‘Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?’ So they took away the stone. And Jesus looked upwards and said, ‘Father, I thank you for having heard me. I knew that you always hear me, but I have said this for the sake of the crowd standing here, so that they may believe that you sent me.’ When he had said this, he cried with a loud voice, ‘Lazarus, come out!’ The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Unbind him, and let him go.’

Many of the Jews therefore, who had come with Mary and had seen what Jesus did, believed in him.

Art Source: JESUS MAFA

Reflections

It might be that one of the most powerful lines in today’s readings is also the shortest. In the Gospel of John we read: “Jesus began to weep.” We might want to begin there; beginning in the middle of the story we hear. A story in which Jesus is set within a network of relationships: the debates with his disciples; the intimacy of close friendship; the wider community of the Jews. At the heart though is a tomb; the tomb of a dear friend. So he weeps.

Pope Francis speaks of today as the “Sunday of Tears”: it is also a day when we see Jesus confront death. The compassion of the tears identifies with us; but Jesus is not overcome by the darkness and finality of a tomb. Instead he confronts it: naming the pain of separation, the disruption of loss, the chaos of grief and giving us a glimpse of what is to come. That in his own passion he will confront, wrestle with and overcome death itself.

Jesus restores life to Lazarus. He restores life to the household of Mary and Martha. The stench of grief and decay is dispelled. They receive back what they thought they had lost. How might they have felt? How might Lazarus have felt?

The Jesus MAFA project captures something of joy and freedom and new life. This is the first-fruit of something greater and perhaps Riley’s image captures something of the mystery of that. For yes, Lazarus will still die to this world; but Jesus, in his Passion will defeat sin, suffering and death.

This story gives a foretaste of that new creation; a new reality is beginning to break in. We are invited to receive it and to share it. But first we must enter into Jesus’ Passion. In our own households, in our own networks of love and care, will share some of the same vulnerabilities and questions of that home in Bethany; might we also be receptive to the love and life and hope Jesus brings.

Martha expresses this trust in an eternal future - of life in abundance - when she speaks of the resurrection; but she and her sister glimpse something of that breaking into human history, into the disruption of grief that they carry. Perhaps this new life is as disruptive as death itself. Certainly those in positions of power feel threatened by it.

We see this life that really is life in the compassion of Jesus tears; in the restoration of a brother to his siblings; we will see it again in the passion of Jesus as he descends from cross to grave. And there too we might wait and weep.

We wait trusting that this life that really is life will burst forth. Romans 8 is one of my favourite passages of Scripture. In today’s reading, we hear Paul exploring this new life. The life of the Spirit dwelling in us. Rather than being preoccupied with the needs of the flesh, we are invited to please God, seeking all that is righteous.

It is life that opposes and overcomes all that diminishes others; it resists the violence of injustice; it strips away claims to status and power; it reveals our vulnerabilities and also our dependence on others. As it does so it reveals the gift of God’s Kingdom - where the need for justice and mercy and compassion

Some are re-naming today as the Second Sunday of Corona-tide. For all the challenges, fears and disruption; amidst the very tangible nearness of illness, grief and death; are we also seeing new life in this shared experience of passion and suffering?

We are seeing a renewed commitment to public service. We witness the numbers offering to be NHS volunteers, the applause echoing around our streets as we showed appreciation for those working safe. There are renewed discussions about a citizens income; a review of universal credit and the resourcing of all that builds up our society.

We’re travelling less and perhaps consuming less. Streets are setting up WhatsApp or Facebook groups to connect those in need with those able to help; we are making more time to speak to those we cannot see. The loss of physical touch is hard; keeping our distance feels strange; but perhaps at a deep level we are relearning a collective body language of both passion and compassion.

One day we will this season of isolation will end. One day we will be able to hug one another again. One day we will look back on this season of grief and pain and the nearness of death; and we will give thanks for the small things we’ve given or received, with love. Even now, as we break bread, may we know what really matters: a depth of love given for us in Jesus Christ.

For now it may feel as if the seeds of that are buried in the ground. Some of you may be planting vegetables, perhaps for the first time; trusting that as those seeds die, they will take root and bring a modest yet rich harvest. Others of us may be watching tree blossom and flowers budding with a new delight. God’s Kingdom too might be hidden, but will spring forth in new ways.

Ezekiel’s vision gives us a very vivid image for this new body language. It seems to the prophet that God’s people are forgotten - their bones lie scattered. He sees an absence of God when there is great need; it is a scene of lifelessness and fragmentation. It seems as if hope is lost.

Yet this desolation is not the end either: the Lord declares ‘I will put my spirit within you, and you shall life’. May this be our prayer for our communities and our households, for our government and our creative industries; for NHS staff and those supplying food; for businesses and free-lancers. May there be life.

Perhaps we might pray especially for those who are anxious and unwell; those who are facing death and having to mourn in ways that are very different in this lockdown season. May they know that they are loved; that there is compassion in their suffering; may they find life and hope. Pray that they and we may know the breath of life; God’s holy and healing Spirit.

Is this a season where the Spirit does make our dry bones live; where we are released from our tombs. What might it mean for us to be set free - to praise God but also to seek the justice of God’s Kingdom?

© Julie Gittoes 2020

Prayers

Lord Jesus Christ,

you have taught us

that what we do for the least of

our brothers and sisters

we do also for you:

give us the will to be the servant of others

as you were the servant of all,

and gave up your life and died for us,

but are alive and reign,

now and for ever. Amen.

John Reilly - The raising of Lazarus (Methodist Art Collection)