Sunday September 25, 2022: Amos 6:1a, 4-7, 1 Timothy 6:6-19, Luke 16:19-31: a sermon preached at St Mary's and Christ Church

Last week began with words from Archbishop Justin on the nature of loving service, those we remember; whereas those who cling to power and privilege are long forgotten [Her Late Majesty's Funeral]. The week ended with a “mini-budget” and an MP [David Lammy] saying ‘I have a joke about trickle down economics. 99% of you won’t ever get it’.

It’s a joke which we know isn’t funny. As the psalmist says, we trust in a God who gives bread to those who hunger, and the poor are still waiting for justice.

A sermon isn’t a lesson in economics or Trussenomics.. Rather it is an opportunity to see our world, its systems and priorities through the lens of scripture. The contrast is stark. Today, we hear of the prophet Amos pointing out that weath and revelry pass - alas, he cries, for those who’re at ease, secure, notable and rich - but who are not grieved at the plight of others.

We hear too from Timothy the familiar words said at funerals: taking us to the heart of the human condition ‘we brought nothing into the world, we take nothing out’ Therefore, we are to be content with food and clothing, and take hold of the life that is life. Loving service now - and hope in death, the gate of glory.

Paul warns the younger man Timothy that love of money can supplant love of God and obedience to God’s commandment: hearts turn inwards, swayed by harmful desires; succumbing to greed rather than generosity, comfort rather than compassion. But riches are uncertain and what we have we should be ready to share.

We know that we are facing a cost of living crisis and that the most vulnerable are already suffering. Putting profit before people and selfishness over stewardship is cruel. As the CEO of the Children’s Society puts it: ‘billions in tax savings for high income earners is going to do nothing to help families bearing the brunt of this crisis’ [from Twitter 24 September].

Whatever our capital p politics, it hurts us to see what God sees; in the words of Amos, we should be grieved at the plight of others. To acknowledge the brokenness and brokenness, the systems of greed and exploitation is part of our call to be capital p prophetic.

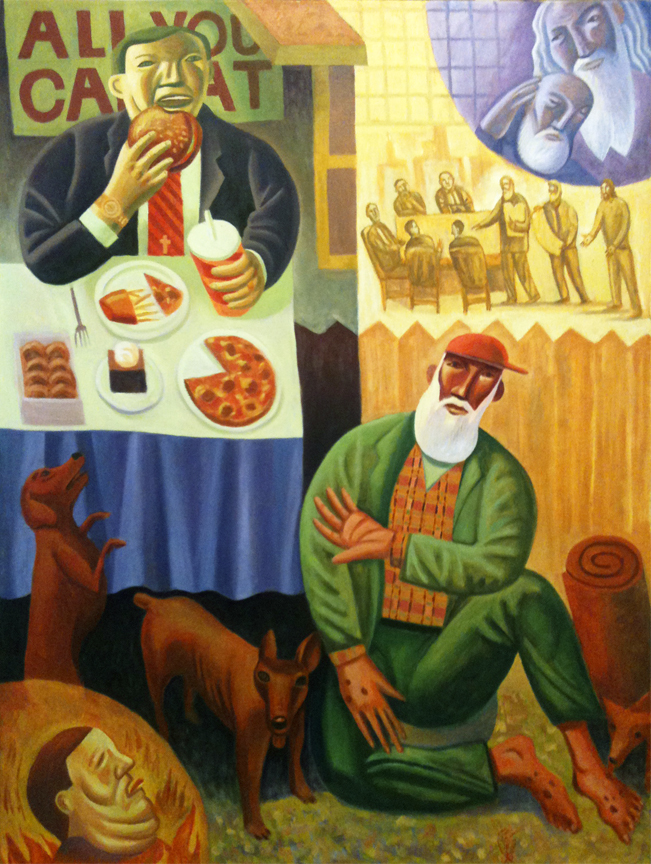

In the parable Jesus tells, the unnamed rich man chooses not see what is in front of him as he feasts sumptuously - he neither acknowledges Lazarus nor alleviates his suffering. Lazarus is visible, human, real; longing for a crumb, consoled by the presence of dogs.

The Rich Man and Lazarus - James Janknegt

In this story, death is the gate of a great reversal: the wealthy, gluttonous foodie thirsts in agony; the poor man is comforted by Abraham. There is a chasm set between them.

Lazarus cannot be sent to do the richman’s bidding: neither in offering soothing water nor in warning his brothers. The wisdom of Moses and the prophets should be enough for us: love God and neighbour - alas for those who are rich.

There is an urgency to this uncomfortable story: it highlights what’s at stake; strips away the illusion that our choices are endless. It’s a story about wealth, the temptations of riches and the apathy induced by material comfort. It challenges us - whatever our financial position - to see the world as God sees it: to see the reality of suffering, need and ultimately human dignity.

The richman couldn't not see Lazarus - he may have considered whether he was lazy or ‘deserving’ poor; wondered what led to his circumstances; tossed him spare change occasionally. He may have considered, as he entertained wealthy friends, how to solve ‘the problem’ of street homeless. He may have noticed him, but not truly seen him.

Jesus invites us to see each other: to recognise our shared humanity, dignity and worth; to see the kinship between us. The one who is God with us, invites us to risk the cost and vulnerability of being in relationship with others; to hear their stories and see in their faces something of our own fear and fragility, indeed our own mortality.

To see Lazarus, the richman would not only glimpse something of his own fractured dignity; to acknowledge his circumstances, privilege and complicity in the suffering of others. To see would be to admit ‘we bring nothing into the world, we take nothing out’; that to cling to power is to be forgotten; it is to be grieved at the plight of others, to be content with what we have and to share.

One of the refrains of Moses and the prophets is that love of God, true fear and awe of God, is the beginning of wisdom. If we show such reverence - to the one in whom we live and move and have our being - we cannot not have the same reverence for others: our fellow human beings who bear God’s image and indeed the whole of creation.

We are all impoverished by the incapacity to grieve the plight of others; by the trading contentment for what we have for craving more than we need; by exchanging short term profit for long term sustainability.

To see in this way demands personal commitment and collective effort. It means finding ways to reduce or cross the chasm between want and plenty - a chasm we create and reinforce through the policies and politics we choose. It is unsettling because it demands courage and imagination, but Jesus subverts the norms and hierarchies we live by, crossing the chasm of life and death to bring new life.

In the book The Spirit Level Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett argue that inequality has a damaging effect on society: ‘eroding trust, increasing anxiety and illness, encouraging excessive consumption’. Equality, they argue, is better for everyone. The Joseph Roundtree Foundation called for more research on the policy and tax implications of their work - some of that includes recognition of our interdependence and need for security; reducing stigma and increasing commitment to the common good.

To take hold of life that really is life might mean bearing the burdens of others, being content with what we have and confronting privilege. We trust in a God who crosses over the chasms we construct and maintain - in Jesus we are shown a way of selflessness and loving service. As Archbishop Justin said, we are shown who do follow - losing our lives in order to gain them.

We have everything we need: created and creaturely goodness; the gift of forgiveness and the hope of blessing; we have the life, death and resurrection of Jesus; we have power of the Spirit gathering us together as one. Dare we offer healing love to our world - in what we spend, in how we protest, in what we campaign for, in who we see and who - and what - we serve. Amen.

© Julie Gittoes 2022