Jeremiah 23:1-6, Colossians 1:11-20 and Luke 23:33-43

Finally, after months of trailers and ubiquitous adverts, The Crown is back for its third season: apparently, the first episode takes exactly one minute and 20 seconds to show us a corgi, which [according to one commentator] is one minutes and 19 seconds too long. Something she’ll forgive because of Olivia Colman.

The words from the lips of Colman’s Queen Elizabeth are: “Old bat”, spoken as she inspects a new portrait of herself to be used on postage stamps. This austere profile, is designed to convey a sense of majesty, marked the queen’s transition from a young princess to a settled monarch.

It's 1964, and in the words of Bob Dylan’s song of that same year: the times they are a-changin.

A General Election is underway. Winston Churchill dies. There’s a a new Prime Minister. There are rumours of Russian interference and of a KGM spy at the heart of the establishment. Beneath the glamour and weight of responsibility there are scandalous shadows of the Profumo Affair. There are discussions of trust and character, of fabrications and truth.

And in this drama, lavishly blending together fact and imagination, the complicated dynamics of power and privilege, service and duty are woven are played out. They casts light on the world we inhabit: the contradictions and struggles of times which are a-changin’. It could well be 2019 as much as 1964.

Today, as we celebrate Christ the King - the feast of title of this church - the images of thrones and crowns, royalty and power are cast in a different light.

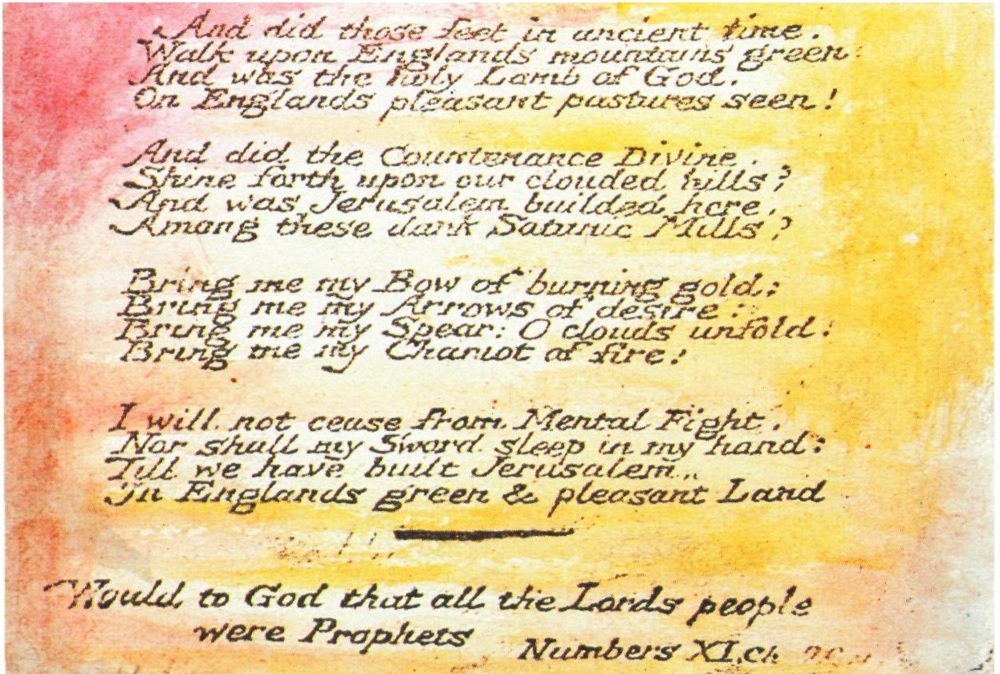

This feast emerged in the Roman Catholic Church in the wake of the devastation of the Great War: it was in a sense a warning about the ways in which human authority could be both seductive and destructive. It was an attempt to place at the heart of public life the principle that Jesus Christ is the only King.

In the words of our opening prayer: Christ’s kingship is about peace and unity; it’s about enthroning Christ as Lord of our lives; it’s about drawing the whole of creation into the life of worship.

Jeremiah has sharp words for those who are entrusted with positions of leadership. The prophet calls out behaviour which is self-serving; and promises instead to raise up a new king. The Lord of righteousness will come with wisdom and justice, ensuring safety of God’s people.

That Lord doesn’t reign from a throne or palace or parliament: instead our Lord reigns with us in human flesh. God is with us in Jesus reigning in a manger; ruling amidst the messiness of our lives, leading us into God’s kingdom of justice, mercy, compassion and peace.

Today we see the reign of love from the very depths of human sorrow and pain.

Today we are invited to gaze upon the face of the one who is our Lord: like those in our gospel, we look, and see and respond.

The inscription over Jesus’ cross is clear: This is the King of the Jews.

It’s an inscription which provokes challenge and questions; silence and indifference.

Some stood by watching. They keep their distance.

Some stood by, gambling: casting lists for his clothes.

Some looked on, scoffing: from the position of their own religious leadership, waiting for a sign; for the ultimate miracle.

Soldiers looked on, mocking him. If you are the king, they ask, use power in the way we understand; use it to save yourself;

A criminal looked on: deriding him. Crying out with that same questioning ‘if’; If you are God’s chosen - do something to set me free.

Three ‘ifs’ echoing the temptations of the wilderness: temptations to use power for selfish ends, to impress others or to collude with the ways of the world.

But there’s another voice. The second criminal. And when he speaks, he sees a different kind of glory and power; he sees victory where there is shame; hope where there is loss.

He speaks out: ‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.’

For although our own mistakes and misdeeds are evident, God in Jesus comes to that place of humiliation and shame and brings the gift of mercy and forgiveness.

So often we are caught up in the regrets and stories of our past that we get stuck there.

Or we get so caught up in our own plans for the future, that we are ensnared by mere wishes.

What we do have is this present moment: and there, as he confronts death, this criminal teaches us what really matters.

A sermon preached at the joint service for Christ the King - celebrating the feast of title at Christ Church. An amazing service - gathering to break bread in worship and break bread in fellowship - expressing what it means to be two churches and one parish.

Today in the present moment we hear, those precious words of promise: the promise of paradise. This is a moment of hope.

We are invited to embrace this hope.

We embrace this hope as we take into our hands the body of Christ: in the wafer thin fragility of broken bread, we encounter the depth of love and the promise of new life.

As we hear in Colossians: this is what makes us strong; this is the source of our patience and joy.

The one who is the image of the invisible God; the firstborn of all creation; show holds all things together. This one is with us.

This God has rescued us from the power of darkness; from all those things which distort power and which corrupt love.

Jeremiah challenges us about the way we exercise leadership: in our homes and in our schools, in our churches and our workplaces, in public service and in our acts of charity.

We are called to bring people together rather than to scatter them; to enable them to flourish in safety rather than leaving them fearful.

For us, as much as for Dylan, we can be sure that times they are a-changin’. The challenge and invitation is for us as Christians to be confidence and faithful in our witness - calling power to account, yes; but also reflecting the fullness of life and love God promises us now, though the power of the Spirit.

Perhaps we can reclaim the new slogan adopted by the Guardian: change is possible; hope is power.

That hope is in Christ: so let us celebrate this feast. Rising to challenge of sharing the fullness of love; and the hope of peace and reconciliation.

Change is possible; hope is power.

He is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that he might come to have first place in everything. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross.

Change is possible. Christ is king. Hope is our power.

© Julie Gittoes 2019