This is the text of a Lent Talk given as part of the "Faith through Art" series at Guildford Cathedral. As a result of tech glitches, we started late and had to rely on a black and white copy of Edwina Sandys' "Christa". This is the approximate text with some additional images and links including Sandys' own site and reflections on "Christa" thirty-years on can be found in an article in the Huffington Post

| Alexandre Getsman and Edwina Sandys in front of CHRISTA Image and interview from New York Social Diary: 18 November, 2011 |

On her website, Edwina Sandys describes herself as a 'New Yorker by choice and marriage'. It is perhaps unsurprising that, given her father Duncan Sandys was a Cabinet Minister and that her grandfather was Winston Churchill, she considered standing for Parliament.

It's even less surprising then that as an artist, her work is very much inspired by political and social themes - including gender. There's a sense of joy and playfulness in her work - whether we are looking at images of flowers or expressions of female embodiment. And in her wit we find wisdom and challenge.

She is most well known for Christa a bronze sculpture of a female Christ figure on the cross. First shown in 1975 it was displayed in a range of galleries and churches before being installed at the Cathedral of St John the Divine (New York) in 1984. As the first such representation, the work created considerable furore - the inevitable outrange and voices moved by the emotional power of the work.

What do we see when we look on this image?

Are we shocked or inspired by the suffering, composure and strength?

The human desire to identify with Christ Jesus in his humanity is an enduring and universal concern.

The human desire to explore what it means for God to be with us in the fullness of our humanity is reflected in a multiplicity of images.

We are provoked to look beyond the pale, male, blond, blue eyed Jesus of some western art, to think about a rich spiritual and religious iconography. Every generation and culture seeking to mark that likeness.

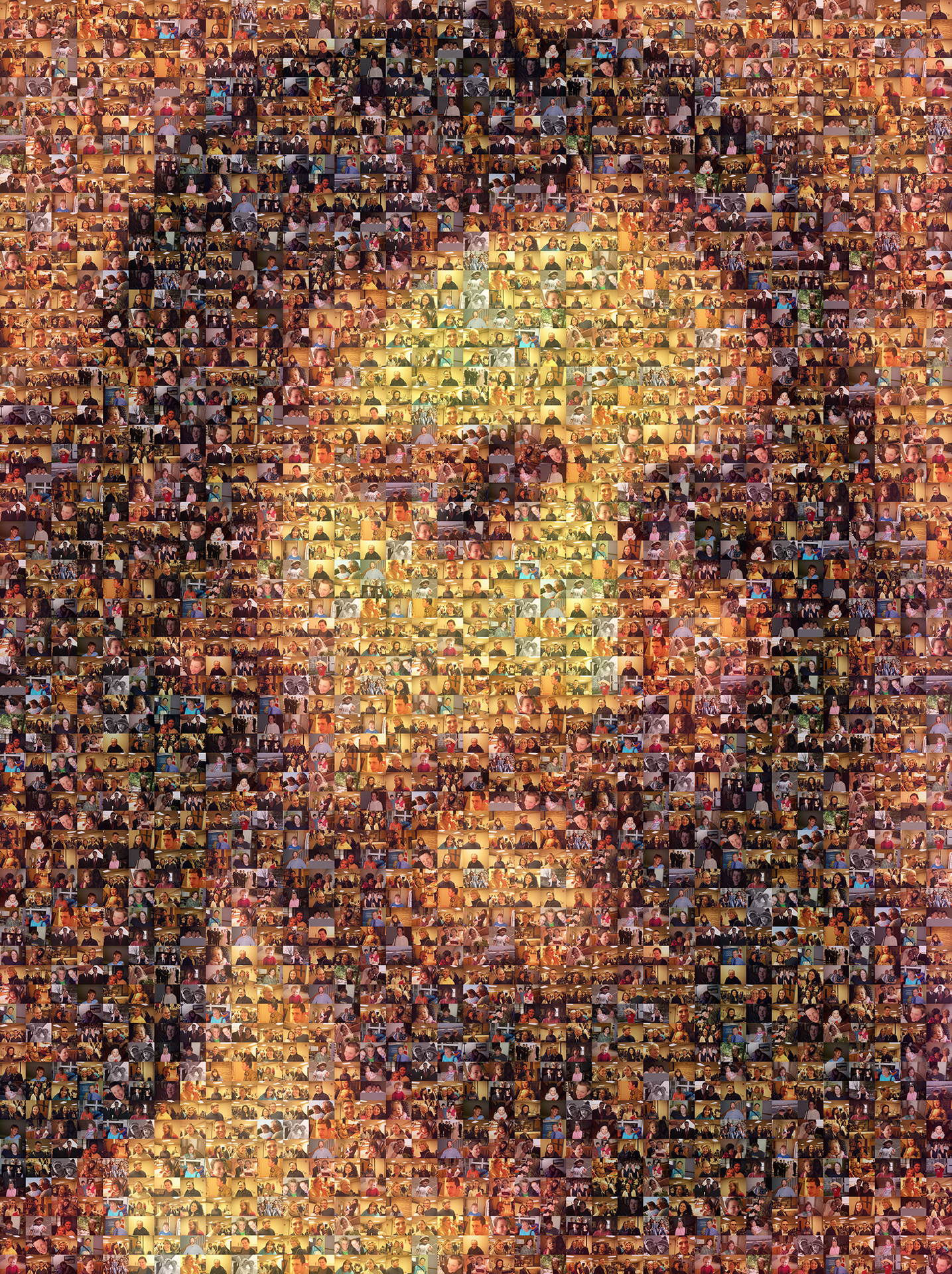

More than that, as members of Christ’s body, through baptism, we want to make visible our ‘in Christ-ness’ as a community; in all our diversity. Whatever our class, occupation, gender, age, health or ability we seek to find our place within this body - to belong, to be accepted and valued. Many artists and projects run by St Paul's Cathedral, for example, have created collages or mosaics taking our faces and transforming them - together - into the face of Christ.

The cross too becomes such a marker of belonging.

The cross is a ubiquitous symbol. Some make the sign as we proclaim the Gospel or before preaching - reminding us of the love of God before speaking/listening. We mark out or see the sign of the cross as we receive the gift of forgiveness and blessing. It is expression of the embodied reality and cost of God’s love poured out for us in Jesus Christ.

It’s a gesture made by lots of sportsmen and women when they prepare to compete: coming on to the pitch, preparing to leave the blocks, taking a penalty.

It’s an item of jewellery: a sought after fashion accessory; a bold statement of faith in workplace; a cherished birthday gift.

It’s a piece of art: an elaborate design tattooed, perhaps entwined with words of faith or a loved one’s name; or for our Coptic brothers and sisters, received at baptism; an indelible mark of being 'in Christ' as in the image below: Coptic wrist crosses

It’s a near universal symbol of Christianity: it is used in worship – in gesture and image; our churches are identified by it in layout and external signage. We literally follow the cross in our liturgy. We receive the sign of the cross on our foreheads in baptism; an invisible sign of God’s grace, God’s yes to us and of our commitment to live in love. It has been, and in some places continues to be, a sign that is controversial, a marker of identity or power; of radical challenge or of conformity.

We follow the cross.

It was not always a marker of Christian faith; rather it was a scandalous sign of brutal and shameful torture. The turning point came at the end of a time of intense persecution in the 4th century. People began to travel to the Holy Land to visit and pray at the places associated with Jesus’ life. Among them was Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine. She oversaw the excavation of various sites and was said to have uncovered a cross, believed to be the cross of Christ.

That discovery, and our devotion, stirs reflection on the breadth and depth of God’s love and forgiveness that we recall in these weeks before Christ’s passion.

Yet sometimes owning a symbol diminishes its power to transform us. A sign of death has become in Christ a sign of love and compassion. Yet we domesticate it; or use it to exclude or marginalize. It is then that we need artists and others to shock us into thinking again about its meaning.

The cross is a scandal.

During her Confessions tour Madonna performed “Live to tell” whilst hanging on a giant mirrored cross wearing a crown of thorns. Unsurprisingly she faced a strong negative reaction from religious groups. Her performance was described as blasphemous, distasteful and heretical.

How should we react? Is it offensive or does her performance provoke us to think about how challenging the cross is?

Madonna’s response to such criticism was to say that her main intention was to highlight the plight of millions of children dying from poverty and hunger in Africa.

As she performed, the death toll of victims is counted on a screen behind her; the words “in Africa 12 million children are orphaned by AIDS” are projected onto the stage. Images of children fade in and out as she sings.

Perhaps it is only scandalous nature of the cross that can do justice to the extent of human suffering today; perhaps it is only the cross that can call us back to our humanity made in the image of God; does the cross provoke us to recall the enormity of God’s love and forgiveness of us; challenging us to respond with repentance and compassion.

As “Live to tell” comes to an end, Madonna steps down from the cross. She kneels, removes the crown of thorns, and bows her head.

In another ubiquitous sign, she adopts the posture of prayer. Above her scroll quotations from Matthew 25: And God said…whatever you did for the least of these brethren.

Whatever you did for the least of these...

How do we respond to the hungry, the naked, the homeless, the excluded, the abused and the marginalized?

God’s love is different: humble, self-giving, generous, challenging and forgiving.

Howe is such love revealed today. To quote Madonna:

How will they hear

When will they learn

How will they know

When will they learn

How will they know

They will hear and learn and know when we ourselves embody the love poured out in self-giving.

I wonder if in part, Sandys' "Christa" serves a similar function to Madonna's live performance.

It provokes us to think about the scandal of the cross; to the scandal of human suffering.

It provokes us to think the reality of God with us: the God who humbled himself to take on our humanity, raises up our human nature.

We are saved - healed, restored, forgiven - through the cross of Christ. The word became flesh: taking on our flesh, male and female.

And perhaps that's the real heresy: denying God's image in us, male and female.

And perhaps that's the real heresy: denying God's image in us, male and female.

After much discussion with those Sandys' called the "earthly powers", "Christa" is now displayed at St John the Divine.

The New York Times

In an interview with Nettie Reynolds in 2015, she said: I didn’t make Christa as a campaign for women’s rights or Women’s Lib as such but I have always believed in equality and I am glad that Christa is just as relevant today as it was in 1975. I didn’t make Christa just for women. Men also suffer and that is one of the meanings of Jesus on the Cross. In the past there were matriarchs in many societies and religions, and gender was not always a factor. Today women are finding their way to take their place in the Christian church and in society in general. Most women of my generation have been stamped with the idea of Man’s superiority over Woman which is hard to throw off without seeming aggressive. I hope that Christa continues to reveal the journey of suffering that we all have in common.

The "Christa" continues to reveal the journey of suffering that we all have in common. Then suffering we share.

As we look at Sandys Christa, might we consider the impact of God’s love revealed in Jesus afresh. He is God with us, alongside us. It also says something about our humanity.

The pursuit of our desires can have a corrosive effect on others: we hurt them by our selfishness, lack of consideration, impatience, anger and unkind speech. The prophets were continually reminding the people of Israel to turn things around – to but God’s love first and allow that to shape our relationships.

But human pride and self-sufficiency gets in the way; we have a human tendency to mess things up. Yesterday, we remembered the martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicity and their companions: the account of their death reduces us to tears.

We hear of their faithfulness and courage; their companionship and dignity. We heard of the bodies of two young women: naked and exposed; then clothed but mortally wounded.

I’d never associated Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem God’s Grandeur with the crucifixion until I looked at this image.

He begins: The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed.

Crushed.

Christ is crushed with us; with our humanity, the generations who have, in Hopkins poem Have trod, have trod, have trod.

Yet glory and grandeur is revealed; the world is charged; recharged with life and beauty.

And the final stanza: the Holy Ghost over the bent / World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Blog: Christa or Christo, Tomato or Tomawtoe

God’s response to our human frailty and cruelty is not to condemn the world but to bring healing and reconciling love.

That gift is something that we are to receive and also embody. It subverts and deepens our understanding of reciprocity in love; it extends to us an invitation to life which is eternal. Jesus life and death are an embodiment of God’s love with us in all the complexity, tension and fearfulness of human life. His risen life demonstrates that our human propensity to mess things up does not have the final word.

Love wins.

The "Christa" calls us to think afresh about the vulnerability and power of embrace: her arms outstretched. We are do likewise.

Reaching out in compassion and speaking out for justice are acts of faithfulness to Jesus. To ignore them and pursue our own ambitions and concerns is the real heresy; denying God’s image in us and in the other. The cross calls us to be with others, not simply doing things for them and returning to our normal lives. It is costly and inspirational.

Does this Christa draw us back to the imagery of God mothering us: gathering us like a hen shelters her brood?

The letter to the Philippians includes one of the earliest creedal statements or hymns to Christ. It reminds us that we are called walk in the steps of the one who did not cling to equality but humbled himself, taking the form of the servant. It means responding to the one who came into the world not to condemn but to save – to redeem, restore, heal and transform us.

The cross is a gesture and a piece of body art; it’s a sentimental item of jewellery and pious religious imagery; it is a statement of faith and a neutral sign of artistic beauty. Ultimately it is a scandal: a stumbling block.

Christa reminds us of the scandal of the enfleshed love of God.

How could it make sense that the God’s Son would be arrested, beaten, condemned and executed as a common criminal?

We have been desensitized to the shame and horror of the cross, a brutal instrument of Roman execution. Instead of seeing the cross as a reminder of God-with-us - amidst the sufferings as well as the joy of the world, we have turned it into a harmless sign; or a symbol of ecclesial piety.

Often Christians have misguided belief that we “own” it – and try to protect it at all costs. However, our ownership of the symbol can be distorted in judgment and condemnation of others. Perhaps Madonna provocative performance focuses our attention on some of the very things Christ was most concerned about; even if she does offend our sense of propriety.

We need to be shocked into being reminded that the cross is a sign of the extent of God’s love for us – giving life for us; that we are to hold on to that as a challenge as we remember all those who suffer and the hurt we cause.

On a global scale it shapes our response to injustice, persecution and violence; at a local level it shapes our response to one another - those we mock or judge; those we undermine or envy. God’s love is different: humble, self-giving, generous, challenging and forgiving. But, to quote Madonna:

How will they hear

When will they learn

How will they know

When will they learn

How will they know

We like James and John are asked: can you drink the cup I drink or be baptised with the baptism I am baptised with? Do we respond with the reckless abandon of those brothers? With the boldness of Peter? Or faithful grief-stricken waiting of Mary Magdalene?

How will they hear

When will they learn

How will they know

When will they learn

How will they know

They will hear and learn and know when we ourselves embody the love poured out in self-giving. What might that look like for you and me as we continue our lenten pilgrimage?

Let us pray.

© Julie Gittoes 2018