Yesterday was my first Sunday at St Mary's and Christ Church: I preached the same sermon in both churches, mindful that as with installing a new piano or organ, I might need to re-voice myself for a new setting. Anyway, there's the grace and gift of time and attentiveness. The texts for Trinity 1 were: Isaiah 65:1-9; Galatians 3:23-29; Luke 8:26-39

I’m not one to dwell on the fashion pages in weekend magazines; and yet I was disappointed that the V&A’s Christian Dior exhibition sold out pretty much as soon as it opened. It traces the impact of one of the 20th century’s most influential fashion houses. Dior’s distinctive silhouettes marking him out as a designer of dreams as a well as dresses.

Clothing plays a significant part in our sense of self and our social interactions: we dress up and dress down; we dress for comfort and dress to impress. There are trends and codes; preferences and practicalities.

Clothing can be a celebration of our personalities and diversity. It might communicate role or instil confidence. But there’s a flip side: clothing can makes us feel uncomfortable or self-conscious. We make judgements about status and well-being.

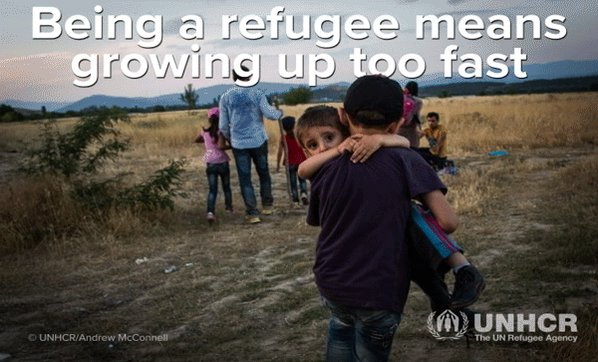

For many millions in our world, it’s the lack of clothing that becomes a marker of displacement. The vulnerability of a hospital gown; kids who dread of school non-uniform days; the needs of rough sleepers; and, in Refugee Week, the desperation and determination of fleeing with the clothes you stand up in.

We don’t have to be Dior to know that our clothing reflects our humanity: our stories, dreams and journeys. We don’t have to go to the V&A to appreciate that our clothing reflects wider cultural dynamics of longing to belong or the impact of trauma, upheaval; the clothing or state of undress resulting from political or economic forces.

In today’s Gospel we encounter a man who is the epitome of such dislocation: he’s suffering from acute mental distress; he’s homeless, naked and at risk.

He is subject to a dark, oppressive and destructive reality. The name ‘Legion’ perhaps hints at the trauma of witnessing the casual brutality of the Roman occupying forces - whose authority serves as possession, control and exploitation.

Having calmed the storms and fears of the sea, Jesus steps out into this bleak place. The Son of the Most High God goes to the place of violence and injury. God’s love is named and made present in this place; powers of cruelty are called out, expelled. After the stampede, there is calm.

The man is clothed; in his right mind. He sits at Jesus’ feet. He assumes the posture of a disciple; one who wishes to learn and follow. A disciple who is being clothed with the character of God’s love.

Towns people and swine herds alike begin to report what has happened, offering perhaps their own commentary not least on the economic impact of what’s happened. God’s work of calling us into new life and freedom is disruptive. And yet, as Jesus leaves that place, the man is called back to his home. His voice continues to speak of God’s at work in Jesus; of new life in him.

There is blessing in this: there is joy and comfort.

In a little while, we will break bread together. We will will pray that in the power of the Spirit, ordinary material stuff will become the means by which Christ will draw near to us. In sharing what is broken, we will be made whole. We become what we already are, his body.

In this place, God calls out to us echoing the words of Isaiah: 'Here I am, here I am’.

In faithful love, God reaches out to us despite our tendency to follow our own devices and desires.

In faith, we reach out our hands to receive the gift of life afresh.

For, as Paul reminds the Galatians: we belong to Christ, we are baptised into Christ, we are clothed with Christ.

We are clothed with Christ. We are one.

Looking beyond outward appearance and status; looking beyond gender, class, ethnicity, sexuality, occupation or health.

We are clothed with the same garment; we are one.

We are heirs of the promise of life: we have equality and dignity before God.

We might not embody that perfectly here an now. Week by week we name our hurts, our failures and our burdens; week by week we lay claim to the promise of forgiveness, healing and new life.

To be clothed in Christ, is to embrace life and joy, love and hope.

To be clothed in this way doesn’t airbrush out our differences in personality or calling; but it draws those things together for a common purpose.

Our generation is not exempt from the powers which seeks to oppress or control human beings; we aren’t exempt with the struggles with imperfection, addiction and brokenness.

And yet God in Christ meets us in that place; and by the power of the Spirit clothes us in peace.

The descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles and Mary at Pentecost

© Elizabeth Wang, radiantlight.org.uk

© Elizabeth Wang, radiantlight.org.uk

Here we are blessed; and from here we will be sent out.

Together we will listen to God and listen to the cries of our world; over time we will discover together how we are being called to respond to our community; how we might offer sanctuary to others.

We might not feel as if we have much influence within the life of our nation: but we have influence where we live.

In the power of the Spirit, we are sent back to our homes and workplaces. We are clothed with Christ, that we might be with others in their distress and in their dreams; in discomfort and determination.

Being clothed with Christ, we are to reflect the love of God: in patience and joy, creativity and kindness; in generosity and hospitality. In those human-scale gestures our character reflects the love of the God who hears the cries of the world. Amen.

© Julie Gittoes 2019

© Julie Gittoes 2019