Monken Hadley: Acts 8:26-end, 1 John 4:7-end, John 15:1-8

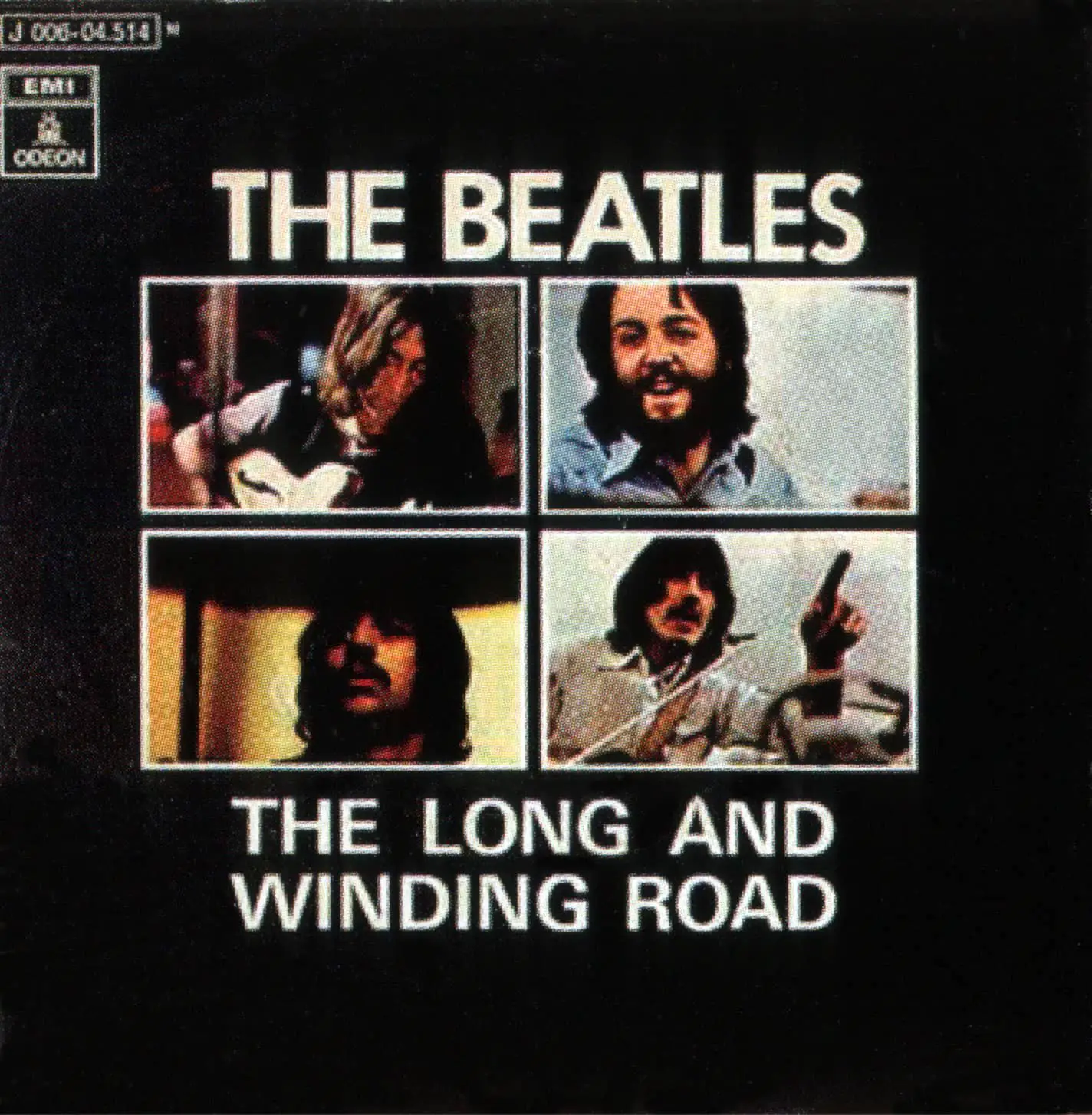

In 1970, The Beatles released “The Long and Winding Road”. Written by Paul MacCartney, and inspired by the sight of a road stretching up into remote highlands of Scotland, it’s a sad song: wind and tears, waiting and loneliness. Decades later, he told his biographer that it was ‘all about the unattainable; the door you never quite reach ... the road that you never get to the end of’.

Roads occupy a kind of in-between space in our lives - literally and metaphorically. Children straining to see the first glimpse of the sea; the rocky roads of adolescence and ageing; the familiar tedium of a commute; the seasons of joy, celebration, waiting or grief. The roads that lead to doors and threshold moments - the many times we’ve cried and the many ways we’ve tried, as the song puts it.

In his commentary on Acts, the black American theologian Willie Jennings describes a ‘road-embedded life born of old and fresh memories of migration, mobility, transition, upheaval and hope’. Naming the particularity of the road from Jerusalem to Gaza, he talks of a road where we are searching for what he calls ‘life possibilities or at least running away from the forces of death’.

For the peoples of Israel and Palestine, those roads continue to hold the fear and horror of the forces of death - the stories shared across the faith networks and fora across this borough; the stories of hostages, destruction and starvation. Yet somehow, stories of life possibilities are still being told - life free from prejudice and complicity - stories told at community Iftas and around seder plates, at vigils and also at every Eucharist we share.

Today we hear that God is found on this road between Jerusalem and Gaza: found there to transform lives with an expansive love, which embraces every soul, every identity and border.

Philip is sent on that road to find the Ethiopian eunuch - to join him, to respond to the invitation to be his guide, as reading the next becomes a communal activity. On that long and winding road, there’s an echo of MacCartney:

Why leave me standing here?

Let me know the way

They begin reading and interpreting a text from isaiah: about a person in pain, a body suffering and humiliated; a body subject to the forces of death. It is this body, explains Philip, that God’s love has been revealed among us.

The Son sent into the world because God’s response to all that wounds and separates us - what we call sin - is to love us. The Son sent into the world to lay down life that we might live; laying life down in order to take it up again; dying to rise and bear fruit. This is the sacrifice that makes one all that was torn and divided.

There is no greater love than this - says Jesus elsewhere in John - than to lay down life for friends. God’s love made flesh calls us friends, calls us beloved; love that invites us to love.

As a result of this intimate, one-to-one sermon, the winding road becomes a borderland, a door to life. The Ethiopian eunuch is brought close to the joy of this extraordinary divine love. He matters in his difference and complexity, his ethnicity and sexual ambiguity. The one whose body is enslaved and put to use, who has responsibility but little power, finds a new future of light and life.

The Ethiopian wants God as much as God wants him: what is there to prevent his baptism, this joining of water and spirit?

Baptism makes visible the depth of God’s love and its redemptive power. By the power of the Spirit, his life is redirected to this love - like us, he is found in the body of Jesus, wounded, risen and glorified. He is in Christ and Christ is in him. He abides in love.

It is this relationship of love and mutual indwelling that Jesus is drawing us into in John’s Gospel. Horticultural imagery is stretched to expand upon the joy and risk, demands and potential of this life.

Abiding is such a rich word: speaking not of the winding road, but the door we open, the threshold we cross and the place we call home. The place where we can dwell long term: it speaks of the relational indwelling of the Spirit and it expresses our life together as friends seeking to be true to Jesus.

And bearing fruit is what we are called to do.John speaks of this with vibrancy and abundance throughout the Gospel - of doing greater works and washing feet, of bread that feeds a multitude, and water turned to wine when our own resources run out.

In all these images, John gives us a way of understanding how we are to live out a pattern of life shaped by the Eucharist. He teaches us about the bread of life - and how we improvise on the command to ‘do this in remembrance’ by our own embodied acts of service.

Today he gives us the image of vine and vineyard - and image of how we abide together. It is an image of stability and trust, of faithfulness and utter commitment to God and others. It is an image that reminds us not only of the last supper, but of the blood shed for us on the cross and the promise of the new wine of the kingdom.

As David Ford writes in his commentary: ‘together the image of abiding, offers readers a way of understanding, deepening and living both eucharist and covenant, centred on who Jesus is, and the call to abide in him.’ It is a call to be faithful in prayer, to face the truth of who we are - and when and where we need to be pruned to be fruitful.

Here as we celebrate this Eucharist, we are pilgrims on the long and winding road of our earthly life: we find abundance in the fragility of a wafer of bread and the richness of wine, bread broken and blood shed so that we might live.

Here the possibilities of life are named - a renewed vision of justice and peace and of love for each other even in, especially in, our difference. Here we name the ultimate victory of love over the forces of death - we are reminded that love casts out fear. Here we are restored and recalled - invited to love the brothers and sister, the strangers and friends we do see.

We love because love is from God and because God loved us first.

Therefore, like Philip we should be confident in speaking and living the gospel of Jesus. Therefore, as John reminds us, we should be compassionate in serving communities with the love of God the Father.Therefore, we should be creative in reaching people with the gospel - walking that long and winding road with them - in the power of the Spirit.

If all that sounds a bit familiar, it is because it is your own hope and commitment set out in your mission action plan. There will be others, who we are drawn to as Philip was called to the Ethiopian. We might not know them yet; they might be close neighbours already: the ones who say to us - don’t leave me standing here, let me know the way.

God is love and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them. Bear fruit that will last. Abide. Love one another.