A sermon preached at Evensong - thinking about optical illusions and Isaiah's challenge to return to the Lord rather than seeking 'smooth words' or 'prophetic illusions'.How might scripture shape our 'faith optic' to ask the right questions in the face of illusion in public discourse.

The texts were Isaiah 30: 8-31; 2 Corinthians 9

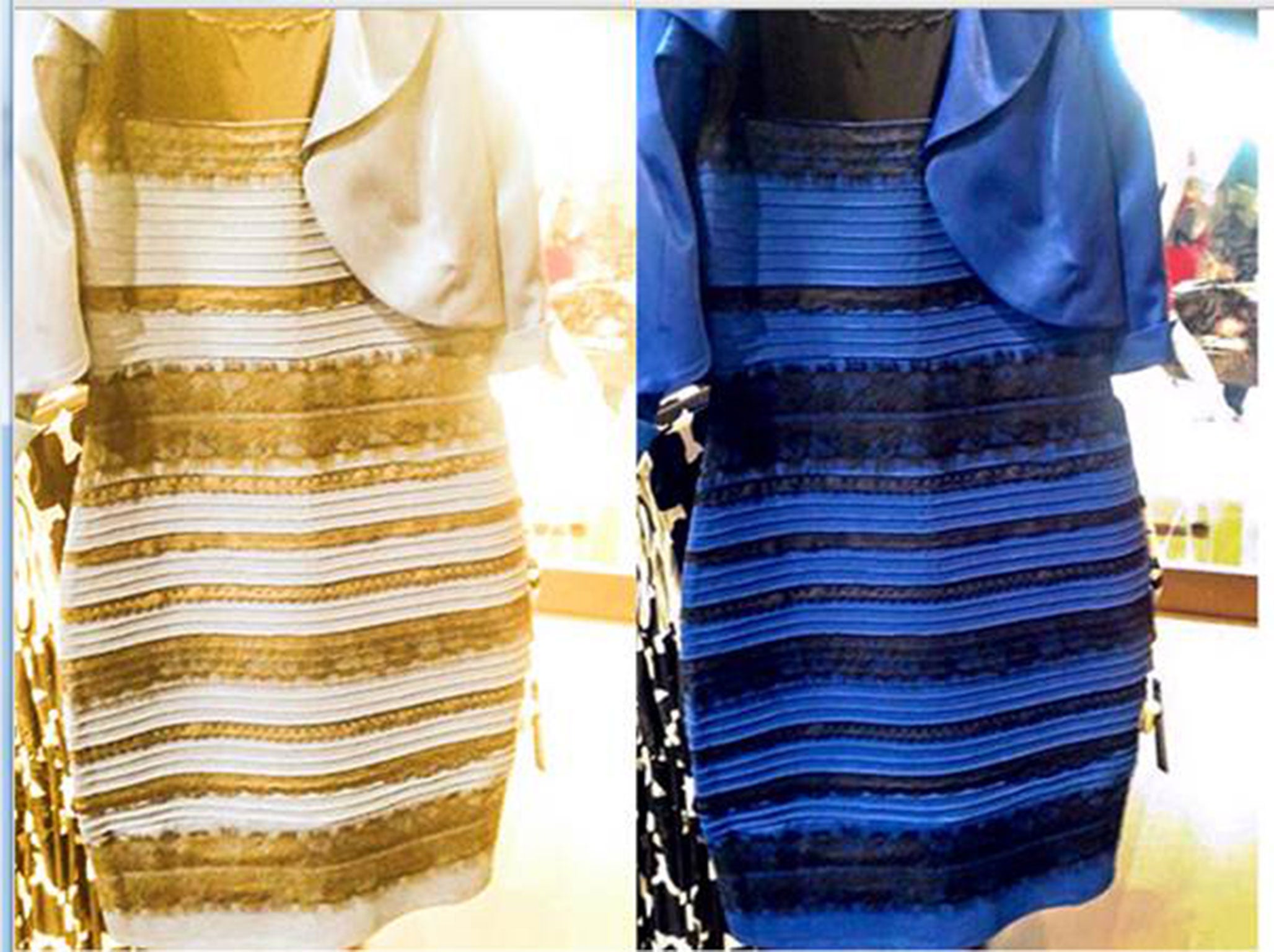

In February 2015, Cecilia Bleasdale took a photograph of the dress she planned to wear at her daughter Grace’s wedding.

After disagreeing about the perceived colour of the dress, Grace went on to post a picture of the dress on Facebook, where friends continued to disagree over the colour they saw: was it white with gold lace or blue with black lace?

The discuss soon went well beyond the small island community of Colonsay. The dress was the the subject of 4.4 million tweets within 24 hours.

Celebrities including Justin Beiber and Kim Kardashian came out on different sides of the colour perception; Taylor Swift said it left her confused; Lady Gaga went her own way, calling it ‘periwinkle and grey’.

The creative director of Roman Originals was gobsmacked by the attention the dress was getting. The company confirmed that it was blue and black; it sold out within 30 minutes of restocking; and the debate continued, attracted scientific not just celebrity interest.

The science of why people saw the same dress differently is complicated: more than on explanation was offered.

It was an illusion: a distortion of the senses or a misrepresentation of the sensory stimulus.

Our brains process colour by relying on two things: the colour of the object itself and the colour of the light source. The image of ‘the dress’ was overexposed. It was partly in shadow, with a blue-ish hue (the blue/black perception); and partly under the store’s yellow lighting (read as white/gold).

Whereas optical illusions can be disorientating but also somehow satisfying - as our eyes learn to read a single image as either a duck or a hare.

It is far more damaging in our social, political or religious sphere. Tonight we hear again words from Isaiah who once more warns Judah about the false promise of relying on Egypt to save them from the Assyrians.

A rebellious and faithless people chose not to see or hear what is right: they want smooth words and prophetic illusions.

Our public discourse is shaped by blogs, data analysis and social media as well as political speeches, policy documents and press interviews: there is so much data and information circulating on climate change, public services and trade deals; surges of protest, activism and debates about democracy.

There are those in the academic realm who talk about intensive explorations of the ‘discourse of illusion within multifarious dimensions of contemporary public discourse’: just the sound of that makes our eyes spin as much as any optical illusion.

How do we resist the siren calls of smooth words and prophetic illusion that tell us that it’ll be alright?

Just as we can understand our optical biases in relation to light and colour, can we attune our spiritual gaze to see more clearly?

Amidst the shadows and back lighting, we can see those things which are oppressive or deceitful; we can place our trust in a God.

The Lord our God waits to be gracious to us.

God’s character of mercy and justice can be our plumb line.

As Isaiah expresses it: In returning and rest you shall be saved; in quietness and in trust shall be your strength.

In the face of adversity and affliction, we can be agents of blessing.

God has set before us a way of love which reaches out to neighbour and accords dignity to each person.

This is the way, Isaiah writes, walk in it.

We read the illusions and truths of our own generation through the lens of love.

A love that multiplies when given and shared. A love that enriches and overflows.

Such love is not politically naive or socially biased: rather it can be a blessing in abundance in the small things; it can be a clarion call of resistance in the big things.

In the face of anxiety and uncertainty, thanksgiving and joy, this love is an optic which brings change, renewal and hope. Let us pray for this gift of grace.

© Julie Gittoes 2019