I'm not a reader of Vogue. I don't think I've ever bought a copy. However, I did come across the September issue for £2; and was intrigued to know how the Duchess of Sussex had got on as a guest editor. The readings were: Jeremiah 23:23-9; Hebrews 11:29-12:2; Luke 12:49-56

The September issue British Vogue has attracted more attention than usual because of its guest editor: HRH The Duchess of Sussex.

The Duchess writes that she and the editorial team have aimed to go a bit deeper to produce an issue ‘of both substance and levity’. So amongst the glossy, high end advertising there are pages on ethical and sustainable brands; features on heritage and history.

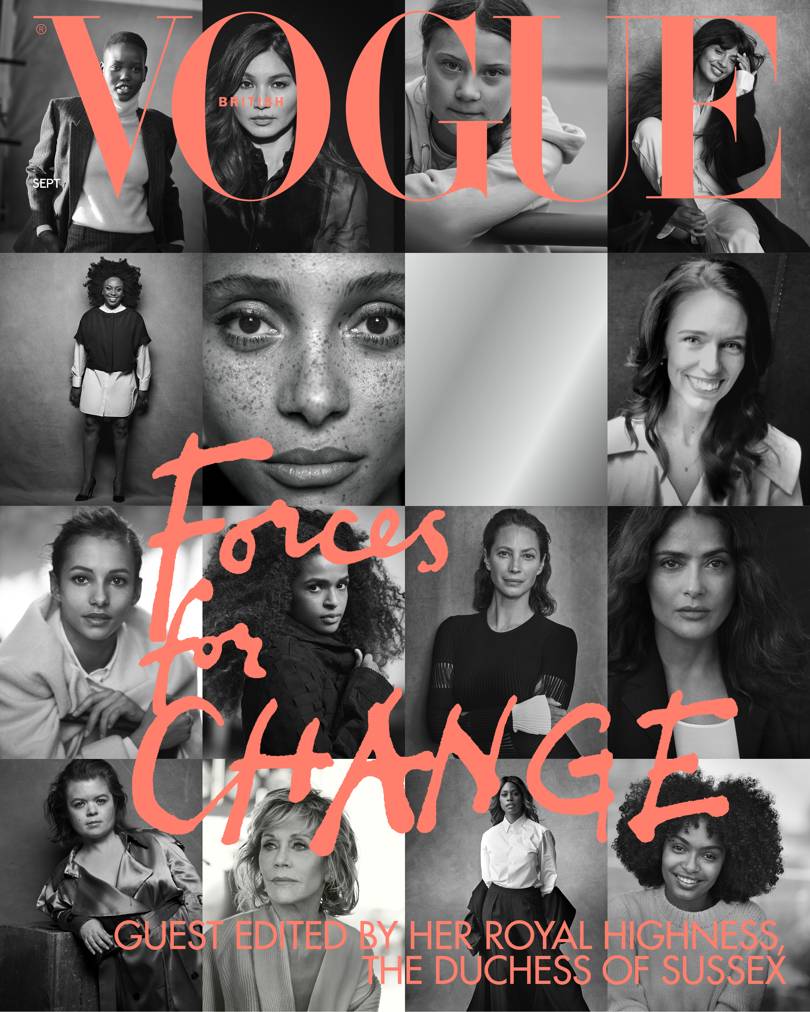

Meghan’s vision was to focus is on “forces of change”: on women who’ve made an impact or who are, in her words, ‘set to re-shape society in radical and positive ways’. Among them are activists, actors, advocates indulging Michelle Obama, Greta Thunberg and Jameela Jamil.

These diverse change-makers are aged from 16 to 81.

The faces on the cover of Vogue span the generations.

Yet so often news headlines speak of generations at war; of stolen futures or neglected responsibilities.

Whether its around housing, pensions or job security; culture, technology or how we vote; the cost of tuition fees or social care: it’s all too easy to pit Baby Boomers against Millennials; to treat successes, failures and struggles as a zero-sum game.

One writer talks about the multiplying effect of rapid change: globalisation, the digitisation, housing bubbles and urban transience. He says ‘many older people have deep roots in their communities but few connections, while many young people have hundreds of connections but no roots in communities’ [Alex Smith on the generation gap].

Such generational divides contribute to loneliness and fragmentation. Add to that the multiplying effects of the tensions and uncertainties around Brexit, and irrespective of party politics or conviction, we face a challenging future. Uncertainty of that sort is the hardest thing to deal with.

Our scriptures present us with challenging words about divisions; and also words of encouragement.

We are called afresh to live by faith.

Elsewhere, the prophet Jeremiah has rebuked those who cry ‘peace, peace’ where there is none. Today we hear further words of rebuke when prophets fail guide people to seek justice and mercy.

Jeremiah is riled by the vague and seductive of ‘dreams’ which doesn’t touch the needs of the poorest; ‘dreams’ which don’t demand anything of the powerful. Dreams which entice people forget their God; to forget the commandments to love.

The offer of consoling falsehoods is damaging to the fabric of society; claiming the nearness of God yet not responding faithfully. Instead they collude with the lies and deceits of the heart.

God is as near to us as our every breath; and yet, also ‘far off’. God’s nearness can’t be treated as a veneer to our social life; the one who fills the heavens and the earth can’t be contained by our agendas.

The God of whom Jeremiah speaks is close to those who are far off. This God is with the widow, the orphan and the stranger.

Jeremiah rebukes to prophets for dreams which lead to forgetfulness and a failure to love God and neighbour. Such forgetfulness divides the generations and fragments society.

Instead, the one who has God’s word speak it faithfully.

This word is a force for change.

Like fire, it burns aware impurities; refining and purifying our hearts.

Like a hammer, it breaks down in justices; strengthening communities across generations.

This word comes to dwell with us in Jesus.

In him is radical nearness, intimacy or proximity: he is with the poor and marginalised and influential; the abused and lonely and the advocate. He is with the child and the widow and the politician; the sex worker and the tax collector and the journalist. He is with the despised and the powerful; the carer and the cared for.

He is with us, saying: the kingdom is near.

He is asking, do you love me?

He is with us, looking on us with compassion.

He is asking, who is the neighbour.

Jesus is God with us yet not contained by us: in our households, workplaces and schools; in our streets, within our political institutions and woven into our social fabric.

Jesus is with us as a force for change.

It isn’t comfortable.

This peace does not imply an absence of division: because it does oppose the injustices and self-interests of this present age.

As Jeremiah expressed, there is a difference between God’s peace and false peace; between the peace which seeks the common good, harnessing the hopes and wisdom across generations; and the peace which colludes with worldly values, deceitfully turning fear into a zero-sum game.

Jesus speaks of his death as a baptism; of the pain, struggle and stress which will be born by his body. For the peace that he brings comes through the shedding of his blood.

He dies to defeat death; he lives to bring new life.

Jesus endured shame for the sake of the joy of God’s Kingdom.

By the cross, heaven and earth are reconciled: God’s love is with us to the end and for ever.

This brings the world to a point of decision: to be seduced by dreams or embrace the Kingdom?

Jesus expresses the choice through the lens of the family.

Family values get interpreted and shaped by wider political and social trends: the hard-working family; the family business; the nuclear family; the family inheritance.

The Kingdom values that Jesus speaks about go beyond biological ties to a vision of kinship where we see others as our brothers and sisters.

Conflicts arise when we witness to that Kingdom because its values challenge personal dreams and deceitful hearts.

This Kingdom is good news for the poor, oppressed and captive; it is at odds with narrow visions of self-interest; it invites us to be forces of change; to advocates and activists for justice, freedom and healing; allowing light to shine in our fragmented world.

Just as we become adept at reading the signs clear skies and storm clouds, we are discern the signs of this Kingdom in our midst.

We do that by faith.

We do that in the company of clouds of witnesses.

By faith we are to be people of peace; and to be just and compassionate.

By faith, we show strength in weakness; being faithful to the promise of life.

By faith, we are to be with the prisoner, the fearful, the lonely, the grieving.

Jesus proclaimed the nearness of the Kingdom in words of rebuke, encouraging and warning.

He also embodied it: in gestures of acceptance and healing; in acts of hospitality and in being with others.

Among the 15 strong women on the cover of Vogue is a mirror: space to see ourselves as part of this collective.

In this Eucharist there is space to be one with Christ: members of his body, agents of his Kingdom.

We are to be forces for change.

Today’s collect reminds us what that looks like: our hearts are to be open to the richness of grace; our lives enlivened and enlightened by the Spirit.

We are to be forces for change: loving, joyful, peaceful; holy, strong and faithful.

Our nation needs courageous Christian witness at a time of at best uncertainty at worst crisis.

As forces for change in every part of our city, how can we make connections and strengthen communities?

Come to this table where the living Christ offers us bread for our journey, for our joys or our tears.

Share this meal together: be the living Christ this week, bringing hope out of despair and truth out of deceit.

Christ calls you by name: in the Spirit, be a force for change.

© Julie Gittoes 2019