Yesterday we celebrated the Feast of Christ the King. As I was preparing to preach - including reading a Saturday paper - I was struck by the ways in which political cartoons seek to provoke and persuade in a world of turmoil. I wondered if parables served a similar purpose - engaging our imaginations to challenge our attitudes or behaviours.

In his commentary on Matthew, the theologian Stanley Hauerwas points out that there are those who ‘claim to need power to do good but in fact just need power’. Our shepherd-king reveals the fallacy of that; and uses the parable of sheep and goats to enable us to reflect on our place in God's Kingdom. The texts were: Ezekiel 34:11-6, 20-24; Ephesians 1:15-end; Matthew 25: 31-end

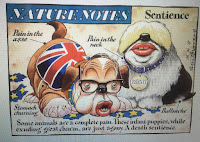

Political cartoonists have an uncanny knack of distilling complex news stories and political agendas into a single image.

Cartoons provoke and persuade. To understand them, we need to interpret the exaggerated symbolism, alongside the captions and characters; we pay attention to the details, allusions and the use of irony. They make sense within the context of a wider narrative or set of situations. The same is true of parables - Jesus uses images and allusions to prompt us to think and act as God’s people.

What might your favourite cartoonist make of today’s parable: nations under judgement, acts of mercy and the division of the blessed and accursed. Who would “Nature Notes” depict as sheep and goats? How would Rowson express eternal life and eternal punishment alongside eternal austerity?

Such musing aren’t out of place. For we, like the disciples, live within the same matrix of earthly loyalties, international upheavals and domestic uncertainties. Like them, we need to learn how to live well in the face of change and adversity, by placing our trust in God’s faithfulness.

The story of the sheep and goats is the last in a series of parables which Jesus deployed in response to the disciples’ admiration of the grandeur of the Temple. As Canon Paul reminded us, Jesus named the transience of worldly powers and impressive buildings; emboldening them - and us - to seek God’s kingdom.

Parables - like cartoons - shed light on our motives, desires and the consequences of our action or inaction. They provoke and persuade us by engaging our imagination - to live without fear, bringing hope to others and acting with mercy. To speak of sheep and goats reveals the impulses of our hearts, our priorities and divisions.

To speak of sheep would evoke passages like those from the prophet Ezekiel: passages which depict God as the chief shepherd of the people: searching and seeking; rescuing and gathering; feeding and binding up; strengthening and judging.

Ezekiel’s words resonate with the human condition. We live in a world where peoples are scattered; where greed, ambition and self-service distorts the responsibility of leadership. His words names our hopes - for a place of rest and safety in our life together. He also names the ways in which we can become divided amongst ourselves - the weak are bullied, the strong exploit their position.

This is the backdrop to Jesus’ parable: a narrative of God’s faithfulness - of a love reaching out towards us, bringing us home. And that love isn’t abstract. Nor is it the cry of ancient prophets alone. This love is revealed in one who is heir of David; the shoot from the stock of Jesse; the one on whom the Spirt of the Lord shall rest. He is Emmanuel.

He taught the crowds on the mountainside and brought healing to those in sickness or distress. Children have been blessed and the rich invited to store up heavenly treasure; matters of divorce, taxation, hospitality and forgiveness have been debated.

Now as we hear the parable of sheep and goats, our generation stands among the nations. We face righteous judgement - standing before the loving gaze of one who is both shepherd and sheep; the king and the one in need.

This parable also sets before us a vision of God’s Kingdom which is marked by showing mercy, loving justice and walking with humility. Jesus words hold leaders to account, but he also calls our attention to ordinary acts of feeding, clothing, welcoming, visiting and caring for others.

Curiously, neither the sheep nor the goats know that in ministering - or failing to do so - that it was Jesus before their eyes. Perhaps our cartoonist would have given them expressions of surprise, shock, joy or embarrassment. Perhaps they too would have added the drama of hell fire versus heavenly bliss to spell out the seriousness of the situation.

The consequences of our action or inaction having enduring impact - on ourselves and others; we can strengthen or scatter, bind up or wound. In this parable, the eyes of our hearts are enlightened. We know the hope to which we are called; the inheritance of faith and love we are to share.

That’s because in these moments, we see and are seen at a level of authentic human engagement; it’s compassion which frees the host and the guest. In going beyond the realm of duty, we see God. In the least of these, we see the Imago Dei, the image of God.

That likeness is embodied and enacted - in face to face intimacy as we counsel the distressed, comfort the anxious and sit with the broken hearted.

This likeness is performed in participation with others in networks which feed, cloth and visit; using gifts to support economic transformation, sustainability and fair trade; in supporting and praying for those who work in immigration centres, prisons and shelters for the homeless or victims of domestic abuse.

The dignity of the Imago Dei is restored as lives and systems are transformed.

Learning to live like this when the future is uncertain is to endure upheaval with our hearts fixed on the victory of the shepherd-king, Emmanuel.

The disciples learn a tough lesson. And so do we. For the one who is God with us, is the least of these. He is stripped of clothing and agency; dignity is crushed, his face smeared with blood and spittle. Hail, king of the Jews!

This king embraced the pain and suffering of humanity in his broken body; his outstretched arms reconciled us to God and each other. In him God’s power is at work - healing, forgiving, challenging, inspiring. As we hear in Ephesians, God’s power raised him from the dead. burst from the tomb, in the silence of the night, to renew our hope that life and death leads to risen life.

Now the one who reigns above all rulers, authority and power, pours out his Spirit on us that we might be united in a bond of peace.

And the most remarkable thing is this: we are members of his body.

We are ‘the fullness of him who fills all in all’. Our agency, our bodies, our breath, our wealth: all this can express the fullness of God’s love in unremarkable yet significant moments.

Here we are fed by that fullness. Here we are called.

Bread broken. Fragments shared. Hands outstretched. Fullness tasted.

A body given that we might be that body.

Then we depart in peace with assurance, hope and challenge of today's communion motet*:

Christ conquers,

Christ reigns,

Christ commands. Alleluia!

* A setting of Christus Vincit by James MacMillan

© Julie Gittoes 2017

_-_WGA19085.jpg)

.jpg)