The second and third reflections from the Good Friday service: what do we see before our eyes as we look on power and customs, on the robe and the crown?

Power and Customs

[John 18:28-40]

1.

They took him: Those who held power and religious authority.

They took him: To one who held power of a conquered people.

Accusations have been made; he is treated as a criminal.

What’s the law, the custom, the penalty?

Who has the power over life and death?

2.

We see unfolding a clash of world views: it begins with a question ‘what accusation do you bring against this man?’

But the fingers aren’t just pointing at Jesus - but at the expectations of custom and the exercise of power.

We see the power of the occupier with the superior force of military might and a system of taxation and exploitation; a system which engendered fear, but which has it’s own fragility.

We see the customs of the occupied with their religious practice and rituals, their beliefs and laws; with the challenge of resentment or collision and the desire for liberation.

Is there a weakness to this power - born of rigidity?

How does it relate to the apparent stability of customs - and fear or confusion?

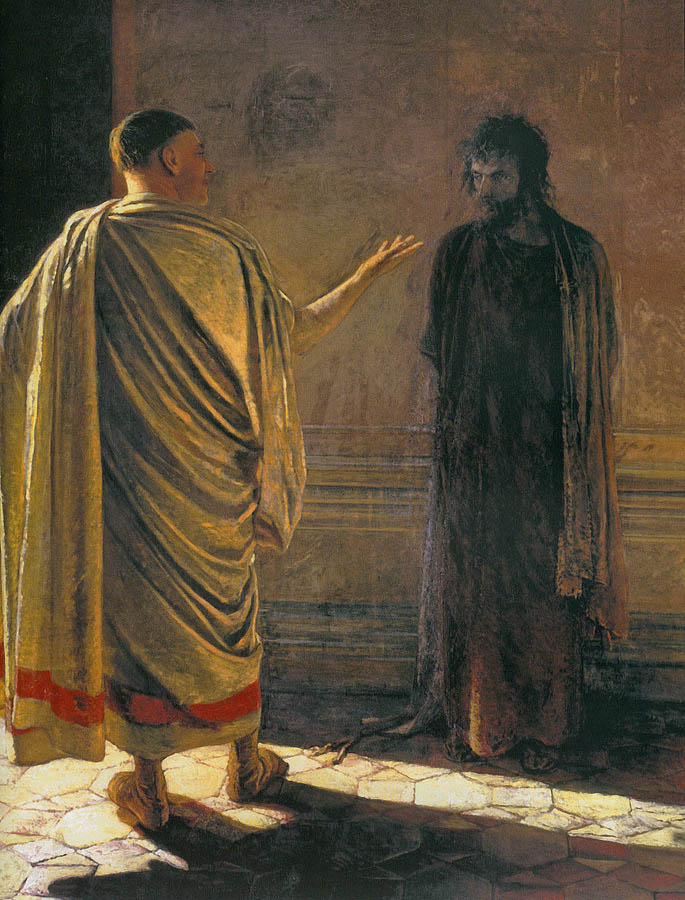

Nikolai Ge - Christ and Pilate (what is truth?), 1980.

3.

They’ve brought Jesus here because his presence is seen as a threat.

He’s the spark which might light the tinder box. The possibility of triggering a revolt would threaten the stability of custom.

What do we see before our eyes?

Jesus’ presence unsettles their spiritual power and the social order. Not only does he raise up the poor and the broken, the curious and marginalised, but he is the Word made flesh.

But the accusations and charges aren’t made explicit: there are assumptions about how much power understands about custom; appeals are made to power to implement custom.

4.

The questioning becomes more intimate, more direct. Earthy power summons Jesus; they face each other

Pilate asks. Jesus replies. They speak of kingdoms and kingship.

Perhaps Pilate is trying to understand: he knows he is reliant on what others say, what he has seen of religion and custom in the place he’s been sent by those who have power over him. Before him stands a King:

King of the Jews?

Do you ask on your own?

What have you done?

Kingdom not of this world?

So you are a king?

5.

A king who is bound, imprisoned and vulnerable.

A king of love.

A servant king who, in washing feet made new the commandment to love.

A king who touched our wounded pride, reached beyond our defences and brought healing.

A king whose weakness communicates love made perfect.

A king of glory.

6.

The one who understands temporal and social power is confronted by one who reveals the truth. The truth of God’s love.

That question hangs in the air.

Truth.

What is truth?

7.

Truth. What is it?

The truth he speaks - the truth he embodies - is the power of love.

That heals and brings new life; which brings freedom. That message is declared by one who is held captive.

He was born for this truth: that in the face of our human propensity to sin we see God’s propensity to reach to the very depths and bring forgiveness and transformation.

Jesus has created space for power to be challenged; for custom to be examined.

Is it an invitation, statement or challenge: belonging to the truth means listening to his voice.

What is truth?

Pilate’s own question hanging in the air - unanswered.

We might speculate: does he want to go deeper or his he wearied by competing claims?

Does he live in a post-truth age? Where expediency and winning the argument, holding a fragile truce become more important?

8

When the voices of power next confront each other, we enter the realm of compromise.

Pilate finds no case against Jesus; but he hands the power of life and death over to custom.

Who will be released: Barabbas or King of the Jews?

What do we see before our eyes?

We face annunciation. Salvation is nigh.

The crowd yells: this all, this one who is God with us yields not to a womb but to a prison.

The one who is immensity in Mary’s womb - and she her Maker’s maker - is refused release.

This all - the alpha and omega - God with us:

Which cannot sin, and yet all sins must bear,

Which cannot die, yet cannon choose but die.

Robe and Crown

[John 19:1-15]

1.

Despite his conviction that there was no case to enter, afraid of the crowds power, gave into their custom.

Pilate wants to let him go: Jesus poses no threat. Perhaps he thinks he’s delusional or an idealist; a good teacher perhaps who’s getting under the skin of the religious authorities.

2.

Perhaps Pilate had hoped to placate the crowd by having Jesus flogged.

They inflict physical harm and humiliation.

The soldiers get carried away with their mockery. Perhaps the’ve heard the cries of the crowd and look on at Jesus and see no threat to their strength and brutal might.

It horrifies us: this routine violence.

Jesus stands alone. Yet he also stands with.

With those who today face degrading physical abuse: today we open our papers and see the violence perpetrated against the gay community in Chechnya; at the start of this Holy Week we heard news of violence against our Coptic brothers and sisters.

Hidden behind closed doors human beings face torture, death and domestic abuse.

The one who is God with us stands alongside them. He has spoken up for them; we too are called speak out against abuse. Who are we called to stand by?

3.

The soldiers see his physical weakness, exhaustion and vulnerability.

Do they think him a lunatic: they take Pilate’s questioning about kingship and kingdoms and twist it.

They mock him in a purple robe; they mock him in a crown of piercing thorns; they mock him in voices of spiteful adulation.

Hail!

Hail, King of the Jews!

They strike him again.

In this way they mock and despise him and those whom he’d come to save: the Samaritan woman, the man born blind, the Greeks at the festival, Lazarus who’d been restored to life.

Pilate takes him and brings him out to the crowd again.

4.

He repeats his decision: I find no case against him.

Does he say it with more or less conviction now? Does he say it with more or less fear of the crowds?

Pilate hopes, perhaps, that this is enough. That this will bring an end to a trial which he does not understand.

Here is the man! he says.

A man. Enough now, surely.

But the chief priests and police alike still cry out ‘crucify’!

Pilate had no case against him. He wants to let him go. To let him go into the hands of those calling for his death.

The final charge is Jesus’ claim to be the Son of God.

This claim made in contempt and fear and derision takes us to the truth of who Jesus is.

It’s a truth that makes Pilate more afraid than ever.

5.

Mockery, escalating tension and provocation leads to fear and compromise. Yet Pilate doesn’t stop asking: does the word ‘truth’ still linger in the space between them?

He asks: ‘where are you from?’

Jesus remains silent.

Silence.

Pilate is caught between the logic of custom and the limits of his power: he stands face to one who is poised yet in chains; the silent Word.

What power does this silent king hold.

Pilate takes this as refusal. As a threat to power.

He knows his own power: the power to release or crucify.

How can he understand this divine rule? A refusal to speak which becomes words of heavenly authority; words which set earthly power in an altogether different light.

Having between these two men is the weight of power: of silence and purpose; of crown of thorns and imperial might; of heaven and earth; life and death; fear and freedom.

6.

Pilate tries to release him.

He hears again the cries.

So many what ifs break in: what if he loses control… what if the crowd overwhelms him… what if he’s removed from a position of power at the edge of a fragile empire?

Religious authority grasps the fragility of his power: his friendship to the Emperor is being tested. Yet what if he acts against justice and his own conscience; where does this lead?

Does it lead to open conflict? Can he suppress outright threat?

Here is your king, he says: your king; he distances himself.

Does he, like Peter, lose his identity? Is this condemnation a denial of sorts?

7.

Truth and love: an eloquent silence.

Pushed to the margins by the clamour of the crowd.

When does fear darken our world leading us to abandon what is just and true?

Like Pilate (and like the crowd) we can become ensnared by our own fears and judgments?

There is no easy forgiveness or cheap grace.

Yet the one who is in chained came as a light to shine in the darkness.

What do we see before our eyes?

Still he proclaims the truth that God is love.

Many fear him, misunderstand him, reject him, condemn him: not wanting to be changed by this love.

Unpredictable earthly power cannot silence the life and hope he brings.

8.

The one who was cloister’d in Mary’s womb came into our world in weakness.

The inn had not room; yet the wise travelled to honour him.

The jealous general doom of Herod is magnified by those in power: in palaces and crowds.

His mother kissed him then and fled to Egypt. We with her share a different woe.

© Julie Gittoes 2017