19 October, Hampstead: Epistles - Genesis 50:15-21 and 2 Corinthians 1:1-7

When was the last time you received a letter - an actual piece of handwritten correspondence? When was the last time you committed thoughts, news or hopes to paper - and posted it to a friend or relative?

For me, it was only a few days ago. My mum writes to me every week. She has done that since I went to university. Comments on the day to day, social events, medical appointments, sermons, family news and what the cat’s been up to.

In that pre-email, pre-mobile phone era, letters were regularly exchanged between friends outside of term - news, trivia, requests, dilemmas. I still have some of them, long after more recent texts have been deleted or email accounts closed. I read of a friend’s hope that her then boyfriend would move to London with her. I re-read it the week before I conducted their marriage.

My dad was a less prolific writer, aside from notes in his work diary detailing hours, the job and how much copper pipe. He wrote when I was at low ebb - the tensions and challenges of a shared-student house. The consolation of a familiar hand; the loving wisdom of a familiar voice. They remain amongst my most treasured possessions; kept alongside the letters of condolence friends wrote when he died too suddenly, too soon.

It goes both ways: letters I’ve written in response to someone else's grief; letters to the Home Office in support of a sibling in Christ; letters written to express thoughts with care. This year I decided to write more, to communicate with my friendship diaspora in pen and ink, not just regular DMs. Choosing the card or the paper, making time; picking up a favourite pen - a tool that might improve my erratic handwriting.

Why? Because letters embody a person; character and emotion come through the text. Whether its quotidian details or a significant moment, a letter is a reference point as we navigate seasons of life. It can be infused with love, faith, gratitude, worries - and prayer. It’s important to take what we write - how it lands, its meaning and purpose.

This kind of labour is a skill and craft, the stuff of flesh and blood. Our communication is more than typing, scrolling and swiping through a digital universe. Letters make our thoughts visible - reclaiming our humanity. There is pleasure in receiving such a gift.

Our first lesson from Genesis speaks into the dynamics of death and history. It names complex relationships - memories, fears, and hopes. It speaks of an instruction. In the circumstances, it is something that’s used like an insurance policy - a way of the brothers mitigating risk or securing a future in uncertain times.

They do not fully trust the expressions of a reconciled relationship between themselves and Joseph. They worry that things will fall apart without their father; that old grudges will reappear, old debts settled.

So they create a ‘letter of wishes’, neither written nor spoken, but nevertheless some plausible final words of a dying man, words of supplication and forgiveness. There are tears on both sides. The grief is real, but so is the story of jealousy, harm, guilt; stability felt fragile, rooted in parental love.

The instruction serves as a catalyst, whereby things do not go unsaid. Past wrongs are acknowledged and forgiveness is sought afresh. In the face of bereavement, space is created to choose to act for the sake of the future. Joseph does not claim to stand in the place of God - but he is able to express the ways in which intended harm was transformed.

His lens is both deeply personal but also attentive to God’s ways with the world: the working out of creative and re-creative activity over time, against the odds; oftentimes hidden, sometimes seen with hindsight, embodied in human life and thought. His words were kind and reassuring; but they point to the future hope and love that overcomes fear.

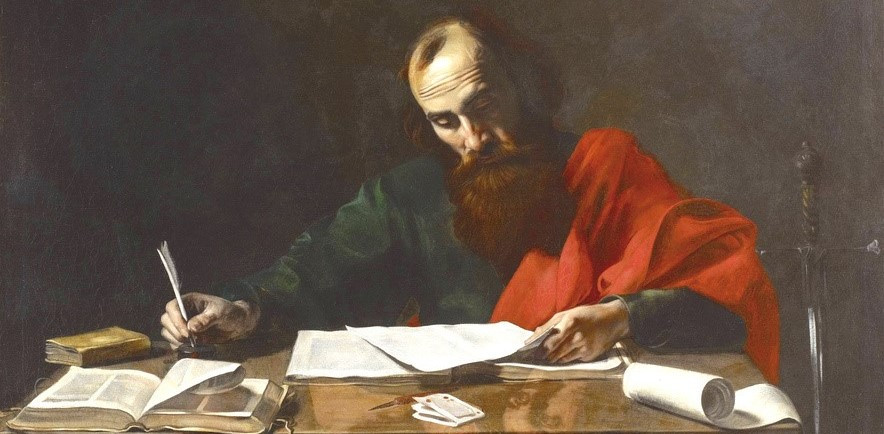

Our second lesson is most definitely a letter. Several times, including in the first letter to the Corinthians, Paul says he’s writing with his own hand. He comments on the large letters he uses, his handwriting marked by all he endures.

The fact that so many letters are within our holy scriptures sometimes obscures the reality that Paul was writing out of all the places we find ourselves. He remembers people by name, asks for prayer and assures his hearers that they are prayed for. He discusses practical arrangements from pleas to share resources with those in need to the return of a forgotten item like a cloak.

He responds to challenges and questions - the tensions within the church and the social, cultural and political norms of the world in which they live; he offers words of consolation or encouragement. Sometimes he gives corrective comments on what he’d heard of their worship and teaching; other times he draws them into words of praise. Part of that was reflected in this evening’s introit - Christ’s life, death and resurrection [Um unsrer Sünden willen - text Philippians 2:8-9 - Felix Mendelssohn].

Once, when experiencing writer’s block in my own work, I decided to read the epistles as actual letters: yes, they are addressed to particular people in particular places - including Corinth and Achaia as we hear today - but they also resonate with us as members of that same church of God. To read them as a whole draws us into their life - and Paul’s thinking.

He’s working as a pastor, evangelist and theologian attending to the mystery of God’s love revealed to us in Christ Jesus - which we heard in Stanford’s setting of Romans 10 [If thou shalt confess with thy mouth - text Romans 10:9-10 - Charles Stanford. He is working out, in pen and ink, what that means for us as members of one body. He is passing on a tradition he has received - of breaking bread in remembrance. He shares his own journey of faith and speaks of how faith transforms our life - the enfleshed poetry of faith, hope and love; the fruit of the Spirit; the radical inclusion through baptism.

Words of grace, peace and blessing frame the opening of today’s letter - a reminder perhaps of how we should greet each other, not just in liturgical expression, but our interpersonal dealings - including our letters. Then, in this very short opening section, we get a glimpse of Paul’s pastoral and theological work. He speaks of suffering and consolation - and finding hope. He takes us to the heart of the gospel.

The mercy of consolation is part of the character of God, made known in Jesus. In him, we are drawn into a movement of both being consoled in our affliction and also offering consolation to others.

What Christ endures with us is also for us: that we might know healing and forgiveness, freedom and comfort in all that we endure. There is no made up instruction - but an embodied reality in the face of our fears, opening up a more hopeful future.

Paul writes his letters on the road, in the company of others and sometimes in prison. He expresses solidarity with that depth of human experience - the pains and griefs and wounds we endure. This is not for him just a matter of empathy but a pointing towards divine mercy. He wants his hearers to hold onto the same unshakeable hope; of God’s love for the world, and the Holy Spirit at work in us.

Paul writes to the Corinthians about repentance and forgiveness, of the need for generosity; about the power of God seen in human weakness. He exalts them to live in love and peace, to find ways to be advocates rather than adversaries. Poignant words in our own generation. He ends:

The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with all of you.

© Julie Gittoes 2015