This is the text of a sermon preached at Evensong at Guildford Cathedral on Sunday, 4th March. This evening also sees the 90th Academy Awards - and of all the films I've seen in the last month Lady Bird was particularly poignant and engaging. In part, it was its very ordinariness which elevated it beyond the usual saccharine coming of age movies.

However, this year's Oscars are also set against the backdrop of the #MeToo and #TimesUp campaign and in the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite movement. It is only when those with power and privilege use their leverage that a culture changes - on and off screen. Being the best in whatever field can’t be divorced from being more socially conscious (Oscars so Right).

Perhaps that’s what the former actor and UN ambassador, Meghan Markle had in mind when she spoke at The Royal Foundation event last week: shifting the focus from wedding planning, she articulated the need to listen to and support the voices of women; to enable their empowerment.

The readings were: Exodus 5:1-6:1 and Philippians 3:4b-14

I want you to be the best version of yourself.

Words of a mother longing to see her daughter, Christine, flourish: to see her become who she is; to negotiate the bewildering and seemingly contradictory impulses of adolescence; to enable her to shape her freedom well. A freedom expressed in Christine’s determination to give herself her own given name: “Lady Bird”.

Be the best version of yourself is a liberating and challenging imperative. It’s struggle which echoes in spoken and unspoken ways, throughout the film Lady Bird - one of this year’s contenders for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

From the152.4 metres of Academy red carpet to the 12, 000 glasses of champagne, the glamour of the Oscars seems to be marked by excess. Now, in its 90th year, an awards ceremony celebrating artistic and technical skill is having to confront issues of whiteness and race; gender and sexual assault.

Campaigns and protests call our attention to abuse and exclusion. We are learning to recognise, name and challenge the misuse of power by some to curtail the freedom of others.

We know what falls short of the best version of human relationships and behaviour. The hashtags, black dresses and compelling speeches have to followed up with action.

It’s not just a ‘Hollywood’ problem: there’s a way to go for us to be the best version of ourselves, our church, our society.

It’s not just a gender problem either: as this evening’s readings remind us, the struggle for freedom - for freedom as God intends it - is an ongoing challenge for people of faith.

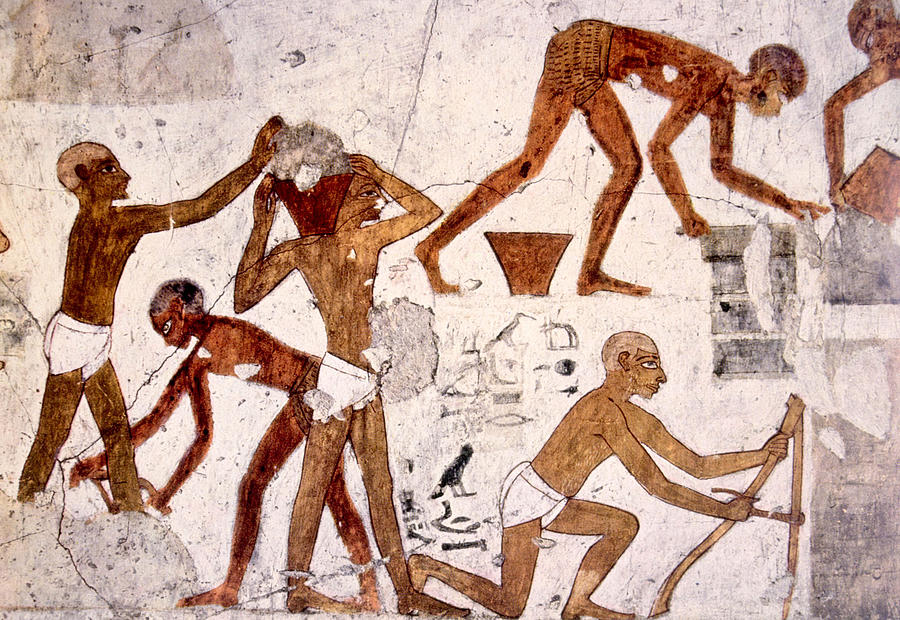

In a single chapter from the book of Exodus, which begins with that great plea “let my people go” we see the grossness of the abuse of power. On the lips of Pharaoh we hear the denial of God and the enslavement of God’s people.

The full weight of the Egyptian system is deployed to lay heavier work on them. Supervisors scatter them to gather straw; task masters demand the same rate of production.

Lazy, lazy, lazy is the scathing refrain of oppressors who overburden. There is no freedom in such coercion - not for the mistreated nor the officials.

Bullying is dehumanising.

Everyone becomes a lesser version of themselves. Pharaoh dismisses the protest; the people turn against Moses; Moses rails against God.

But Time’s Up. God says: he will let them go.

He will call his people into freedom: they will embark on a journey of discovering more and more about God’s ways; grappling with what it means to obey God’s commandments of love; using their freedom to protect the widow, the orphan, the stranger.

I want you to be the best version of yourself

Part of our Lenten discipline that we can ponder anew God’s call to freedom: a call which is itself a gift of creation; indeed a risk of God’s love towards us. A gift that is good - making every act of generosity and every gesture of compassion something precious. A gift, used wisely, which liberates others.

This gift of freedom is fraught with risk: it is so much easier to do what we want; to focus on our hurt, and to hurt others; to hide behind our own opinion or status; to avoid the cost of consensus; to demand of others the additional burden of collecting the proverbial straw.

And yet, as we have seen over recent days, adverse weather can reveal the best version of our society. As Newcastle Cathedral opened its doors to rough sleepers; as volunteers gave away hats, sleeping bags and hot water bottles; as St Mungo’s worked with Bristol Council to co-ordinate emergency provision.

I want you to be the best version of yourself.

You. Me. God’s people. God’s world.

This enlarged vision has small beginnings. And it’s where Lady Bird offers us some clues. The New York Times describes it as “Big Screen Perfection”: and it achieves this not by being an escapist spectacle; but by paying attention to the little things.

This is perhaps one of director Greta Gerwig’s greatest gifts. She knows her characters and the town of Sacramento very well. As a critic puts it: ‘Her affection envelops them like a secular form of grace: not uncritically, but unconditionally’.

Lady Bird seeks to be the best version of herself - raging against perceived injustices and enthusing over new possibilities. Her emotional and spiritual flourishing is tinged with the idealism and hypocrisy, selfishness and generosity that we know all too well. She like us, is met by the patient intimacy of love which is not uncritical, but unconditional.

We see that love in human form: parent, teacher, friend, priest, sibling; and the joyous nun who gently points out to her that love and paying attention are perhaps the same thing.

If Gerwig’s human affection acts as a secular grace, how much more does God’s grace enfold, challenge, sustain and strengthen us? How much more does that gift bless our freedom - shaping the best version of who we are?

It is this gift of grace that Paul writes about to the Christian community Philippi. He writes about freedom whilst under house arrest. His words focus intensely on the joyful liberty he finds in Christ.

He greets the Philippians as faithful and generous people; he prays for them that they might grow in faith; that their lives might be shaped by the breadth and depth of God’s love for them. He shares news with them; offers them advice and encouragement.

He reminds them that the basis of their freedom is in the self-emptying love of God revealed in Jesus Christ. He did not cling to equality with God; but took the form of a servant. Our freedom is in the one who in his own suffering and death not only shared a lived human experience; but freed us from their power.

In him we are reconciled to God. In the world of social media campaigns #LoveWins #TimesUp on all that distorts God’s image in us.

No wonder that Paul is able to sit so lightly to his inherited privileges: his observance of the law, his purity of descent, his membership of the elite and even to confess his own zeal in persecuting others. Salvation - life, healing, freedom, forgiveness and joy - is by faith; it is not faith plus human achievements, good works or power.

It is by grace alone that we have this freedom to be the best version of who we are in Christ. The challenge Paul lays before the Philippians and before us is to live out of this new reality. Having encountered the love of God in Christ Jesus in Scripture, prayer, fellowship, teaching, acts of compassion, we are called to live differently.

In the power of the Spirit, we are to be the best version of ourselves, individually and together. The power of the resurrection is to be made known in our lives; in these bodies.

Breath by breath our God given freedom can empower others - celebrating them, valuing them, challenging them, listening to them.

Moment by moment, that grace is at work in us as we freely give; freely love; freely listen; freely speak out.

Let us pray for grace to keep Lent faithfully: by self-examination, repentance, prayer, self-denial, mediating on God’s holy word and intentional acts of kindness, may we be the best version of God’s people.

© Julie Gittoes 2018