Marr uses the forceful language of being imprisoned to describe the impact of our personal circumstances. Our attitudes, concerns, convictions and priorities are shaped by our families and friends, our experience of education and employment, our health and responsibilities for others. We inhabit a series of emotional, physical and social locations, if you like. But by God's grace they need not limit us. In him, we are called into an everlasting covenant. It's an eternal relationship of love in which we abide and in which find our identity. It's a love which draws us into relationship with others - enabling us to take risks in hospitality, trust, forgiveness and service.

The vision of Isaiah, picked up by Jesus, acknowledges the givenness of our human situation - as individuals and as a society. That's a vision of liberation.

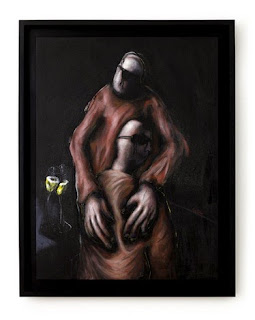

Chris Gollon - Return of the Prodigal Son (2007)

After a period of oppression and exile, Isaiah declares to God's people a message of restoration for the broken hearted: mourning, oppression and captivity are replaced with gladness, praise and a rebuilt city. In this restored world, the people of God have a distinct calling to witness to the love and faithfulness of God. Material wealth is enjoyed and strangers share the work of shepherding and farming.

The Lord's love of justice means that there will be recompense for the victim; those who do thwart God's ways are held to account. Isaiah roots abundance in the praise of God. It is deep attention to his love that enables us to bless others as he blesses us.

Jesus takes up this text as a paradigm for his mission. He goes back to his own geographical and class location - he returns to Nazareth where was known as the carpenter's son. He goes there filled with the power of the Spirit - he goes there to reveal that he is God's Son, the one who fulfils the promise of God's kingdom. He comes to bring release from all that imprisons us.

God's purposes and human hopes are fulfilled as this new era of freedom breaks in. Release begins with forgiveness. God's forgiveness of us entails a restoration of relationship between humanity and God. In Christ's life, death and resurretion sin is defeated. Our perceived status as victim or oppressor no longer determines the future. Forgiving isn't forgetting. It is remembering but refusing to perpetuate the hurt we've suffered. It is a new beginning.

The release proclaimed by Isaiah and fulfilled in Jesus Christ is about deep healing. It operates at a spiritual, personal and social level. This is good news to the poor. Luke does not just define poverty in terms of economic status. He is concerned with all those 'locations', to use Marr's phrase, which imprison us.

Luke tells us of Jesus's encounters with the rich young man and the tax collector; he writes of shepherds and lawyers; he tells us stories of a widow, a samaritan and a prodigal son. All these people are the object of God's love and compassion, forgiveness and blessing. In our own diocese, the poor - those imprisoned by their emotional or physical location - will include the harassed commuter, the victim of domestic abuse, the overstretched care worker, the person whose benefits have been cut and the entrepreneur risking capital on a new project.

In a world of intense pressure and deep longing we are called, like Luke, to share a message of freedom, release, hope. He understood his context and responded to the way power or poverty imprisoned men and women. For him, Jesus Christ is the one who offers dignity and grace - drawing us into a new community. For him, it's the power of Spirit that compels Jesus' followers to go into the world as agents of blessing and reconciliation. Across our diocese, men, women and young peole are responding in manifold ways; in churches, workplaces, families, communites and voluntary service.

Whatever our circumstance or profession, we are called to reach out in acts of generosity and compassion to bring release; to speak words that convey God's purposes not worldly values, challenging systemic and relational injustice . Today we look forward in expectation to the outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost: when we will be anointed, equipped and sent out afresh into our world.

I will end with a reflection on the work of Jean Vanier, founder of the L'Arche community. Speaking on Radio 2 today, he said, we live in a culture of winning and being a success; those who are physically/mentally vulnerable are told they are no good. Life at L'Arche means finding acceptance, encountering difference, having fun and loving with the heart. We are born weak and will die weak he said; but facing our vulnerability with others brings strength and freedom.

This is not just a visionof the church but of God's Kingdom. To be human is to be made in the image of God. Politics, wealth or background should not divide, imprison or classify us. In the power of the Spirit may we bear witness to the love of God made manifest in Jesus Christ.

© 2015 Julie Gittoes