19 October - Trinity 18: Genesis 32:22-31, 2 Timothy 3:14-4:5, Luke 18:1-8

But in the desert darkness one has found me,

Embracing me, He will not let me go,

Nor will I let Him go, whose arms surround me,

Until he tells me all I need to know.

Words from Malcolm Guite’s poem about Jacob wrestling. He’s in a dark place. Alone. He carries the weight of burdens from the past. He is wrestling with God and himself; with the relationships he needs to mend and the guilt he wants to let go of.

Jacob wrestles with a love that will not let him go.

Many threads of today’s readings draw us into moments of struggle; and of a God who is with us in the midst of that. We glimpse something important about persistence in faith, wrestling with questions, grappling for justice.

Jacob wasn’t the first or last to wrestle with another. Wrestling is probably one of the oldest competitive sports in the world - with depictions found in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome.

Whether in the original or modern freestyle, the rules for matches are pretty similar as competitors wrestle with each other - executing holds and techniques.

There is one church in Bradford where faith and wrestling come together: Bible stories combined with body slams, where ring drama meets real-life hope as their website puts it. Through events and services, their mission is to help people encounter the love of Jesus through the art, drama and raw energy of wrestling.

On the BBC’s “Songs of Praise”, Gareth ‘Angel’ Thompson explains why he opened this ministry to help those who may have been ‘forced to navigate difficult childhoods and volatile family situations. He says, ‘you look at the word ‘wrestling’ - they are wrestling with their demons, insecurities, their past, their circumstances.’

Like Jacob before them, physical wrestling is also a moment of grappling with deeper questions: faith and life, relationships and healing. In the vulnerability of encounter, change is possible. He wrestles his way to grace and hope.

Guite’s poem about this life-changing encounter as he wrestled with an angel: his name changes and his future opens up. It is a moment that occurs on his way to his meeting with his estranged brother Esau, who he had wronged.

There is pain in the wrestling, and wounding; but there is also the possibility of reconciliation. He wrestles all night and walks away limping, but also blessed. In the struggle, God meets him and refuses to let him go; in the grappling of body, mind and spirit, his heart is filled with a love.

As Guite reminds us, our lives have glimpses of this story too. He says: 'in our brokenness and alienation must also wrestle with, and be changed by the love that wounds and heals.’

It’s not that such stories sanitize struggle, minimising the uncertainty and cost. Rather they sanctify it - bringing relationship rather than separation. The wrestling fosters advocates rather than adversaries.

Today’s readings aren’t only about the wrestlers who refused to let go, who see blessings emerging from the bruising. It’s also about those who are persistent - the widows and prophets who cry out against injustice.

Jesus tells a parable about the need to pray always and never lose heart: she refused to give up, to stop knocking, even when faced with indifference and a system rigged against her. Hers is a holy defiance in a world of justice delayed.

It’s a story that speaks about persistence in personal faith but also questions of public justice. It’s a parable of protest and liberation - of God’s preferential option for those on the margins. It reminds us that God is with us not just in the holiness of the sanctuary and the holiness of our streets.

Maybe we need a parable like this in our own generation: resisting the disappointments and confronting exploitation and refusing to let go of hope. He encourages us to pray. Persistently.

The judge mocks God’s justice and the woman before him. The judge is the mirror opposite of what we hope for in a judge - wielding power not mercy. The woman represents a lack of ‘clout’ but she embodies the determined cries of the prophets. Her relentlessness makes the judge relents.

In the story Jesus that Jesus tells he doesn’t identify God with the most powerful character in the story. He invites us to open our minds to other interpretations.

On the one hand, he is making the point that if this judge will eventually concede and respond to the cries of the aggrieved, then how much more will God bring in a reign of justice. How much more will God answer our prayers and respond to us with love and care.

On the other hand, we can turn our attention away from the judge and towards the widow: her persistence when she is fobbed off is a different kind of wrestling. Her boldness and faithfulness, her courage and determination put her on the path of change. Her concern for justice seeks life in the face of forces of death.

We too are caught between powers of domination and impulses of compassion. We wrestle with our insecurities and pasts and circumstances. We wrestle in the wilderness and darkness, in the streets and public spaces: love endures in the struggle.

God is there beside us when we limp; whispers hope in the tensions. Wrestling is honest: there is embrace. God does not let us go, until we know what we need to know. These are perhaps holy words for a weary word.

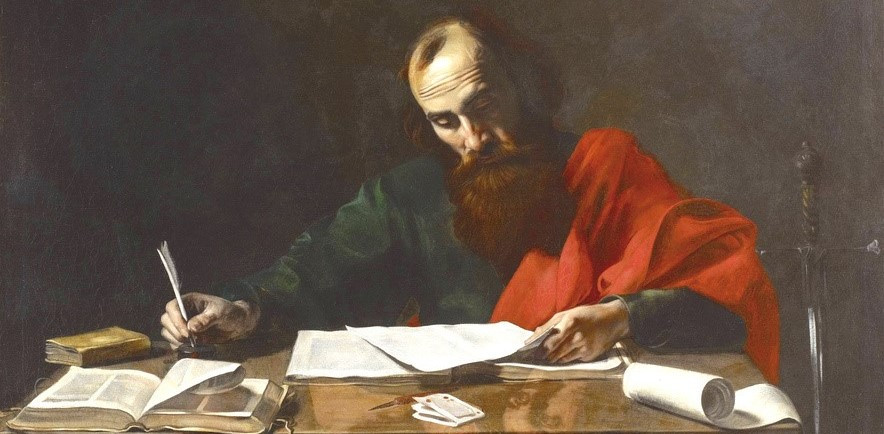

This is where Paul leads us when he writes to Timothy: reminding us that to read the words of scripture is to find forgiveness and freedom. Those words draw us to the living Word, Christ Jesus himself. The one who speaks love not fear.

And we too are to speak: to announce this life-giving; to bear witness to it in our lives. We proclaim and persuade - to put faith into practice, giving an account of the hope that is in us. That means our conduct, our aims, our patience and our commitment is to wrestle - to grapple with the hard work of reconciliation - and to discover the raw energy of our faith.

We come back to scripture; we come back to the altar. In persistence and patience, being changed by the love of our wounded healer. Here we mercy and comfort - in order that our witness might grow through the breath of the Spirit of God.

I dare not face my brother in the morning,

I dare not look upon the things I’ve done,

Dare not ignore a nightmare’s dreadful warning,

Dare not endure the rising of the sun.

My family, my goods, are sent before me,

I cannot sleep on this strange river shore,

I have betrayed the son of one who bore me,

And my own soul rejects me to the core.

But in the desert darkness one has found me,

Embracing me, He will not let me go,

Nor will I let Him go, whose arms surround me,

Until he tells me all I need to know,

And blesses me where daybreak stakes its claim,

With love that wounds and heals; and with His name.

© Julie Gittoes 2025