This is the text of a short reflection given at the Interfaith Panel Discussion convened by Canon Dr Anthony Cane at Chichester Cathedral as part of International Day of Peace. Further details about the event and other panelists can be found on the Cathedral website. The title for the discussion was: How can we live better together, for the well being of all?

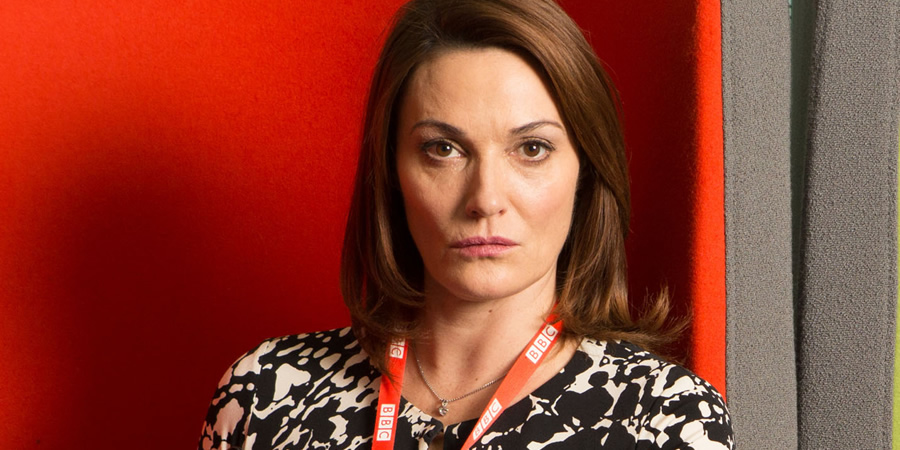

W1A is back!

The BBC comedy sails painfully close to the truth of PC or PR-speak corporate culture with all the anxieties about Charter renewal and public service. W1A parodied what we mean by “better” by appointing of Anna Rampton as Director of Better to place betterness development at the core.

Series three goes one step further as Anna introduces the more of less initiative: as she says, “identifying what we do best and finding more ways of doing less of it better”.

Putting the words ‘better together’ into Google reveals something of our contemporary longing to live well: it’s associated with our digital lives, increased connectivity and the desire for stable personal relationships; it embraces the tension between increasing GDP and the concern for sustainable development; it touches on climate change, the environmental and our political aspirations. There’s talk not only of soft, hard or smooth Brexit; but a better Brexit.

The referendum revealed fault-lines within our society: home owners versus renters; millennials versus pensioners; north versus south; rural versus urban; rich versus poor; graduate versus non-graduate. We can add to this questions of identity - as fluid or sharply defined and inequalities of social and cultural capital, as well as wealth.

In the midst of this, I want to suggest some wisdom from scripture before our conversation:

A line from Psalm 118 [verse 8]: ‘It is better to take refuge in the Lord than to put confidence in mortals’. Psalms draw our entire life under the rule of God - from sorrow and lament to joy and thanksgiving. They represent a struggle for justice and yearning for peace; they express our primary orientation to God. Even in the face of upheaval and distress we are called back to discover a new way of living, rooted in God’s faithful love.

Fixing our attention on God shapes us: our priorities are transformed as we seek to live wisely moment by moment; as God’s ways become our ways. In our relationships and responsibilities we make decisions: to act selfishly or with compassion; to possess and consume or to be content with less. We’re called to seek the welfare of the widow, orphan and stranger. As Proverbs puts it [16: 8]: Better is a little with righteousness than large income with injustice’.

Attentiveness to God and attentiveness to the needs of others is also at the heart of the Gospel. Luke draws us into the dynamics of two siblings - Mary and Martha - who welcome Jesus into the hospitality of their home. One sister is busily consumed with tasks and a grumpy irritation that she's doing it all; the other sits in rapt attention at the feet of her Lord.

Into this tension, Jesus speaks with affection [Luke 10:41-2]: ‘Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things; there is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part…’. Our ability to attend to the needs of others begins by loving God above all things and extends to loving our neighbour fully, even as ourselves.

Into this tension, Jesus speaks with affection [Luke 10:41-2]: ‘Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things; there is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part…’. Our ability to attend to the needs of others begins by loving God above all things and extends to loving our neighbour fully, even as ourselves.

It’s this way of being with others, as God was with us in Jesus, that shapes a Christian tradition and challenges selfish ambition. In Philippians this is seen as key to living better together; enabling all to flourish; to seek the good of the communities in which we share; to be concerned for the interests of others. Concentration on the self pushes others to the margins; instead writes Paul [Philippians 2:3]: ‘Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves.’

How do we live better together, for the well-being of all?

Pay deep attention to God’s loving ways: in prayer, worship and learning. Those habits shape us - so that we might become more who we’re called to be. More loving, generous, compassionate and peaceable; more able to see the other as beloved by God, to seek her well-being.

Like the Director of Better, we identify what we do best…

…but perhaps we should do more of it - for the sake of all - together.

This is the stuff of God’s Kingdom.

To participate fully in the practices and processes which build community, attending to what God is doing in and through others in the places where we live; strengthening networks of faith and good will. This is a rooted, social and authentic way of building trust and renewing hope; looking beyond self interest to a more sustainable and equitable future.

© Julie Gittoes 2017